Create an account

Welcome! Register for an account

La password verrà inviata via email.

Recupero della password

Recupera la tua password

La password verrà inviata via email.

-

- container colonna1

- Categorie

- #iorestoacasa

- Agenda

- Archeologia

- Architettura

- Arte antica

- Arte contemporanea

- Arte moderna

- Arti performative

- Attualità

- Bandi e concorsi

- Beni culturali

- Cinema

- Contest

- Danza

- Design

- Diritto

- Eventi

- Fiere e manifestazioni

- Film e serie tv

- Formazione

- Fotografia

- Libri ed editoria

- Mercato

- MIC Ministero della Cultura

- Moda

- Musei

- Musica

- Opening

- Personaggi

- Politica e opinioni

- Street Art

- Teatro

- Viaggi

- Categorie

- container colonna2

- container colonna1

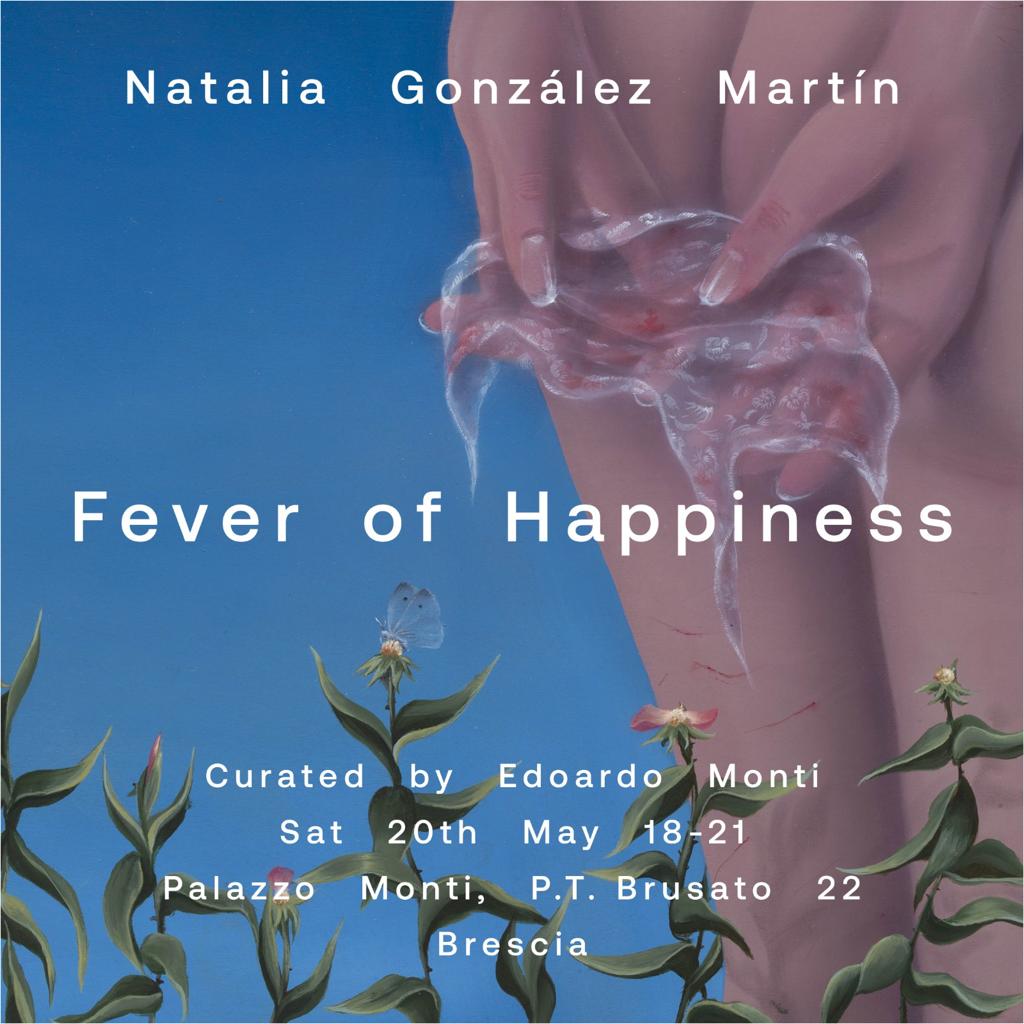

Fever of Happiness

The show presents new works by Gonzalez Martin, created during her residency, alongside new works on paper. Borrowing the formal qualities of icon painting, Gonzalez Martin’s work explores the inscriptions of a shared cultural heritage and moral codes on one’s physical body. Curator – Edoardo Monti.

Comunicato stampa

Segnala l'evento

What is Art, if not the expression of ideas and emotions through a physical medium? Well, Natalia González Martín (b. 1995, Madrid) helps us grasp this simple yet meaningful concept with a practice that is as contemporary as it is rooted in the past. For the artist’s first solo show in Italy, she presents a series of works on panel and paper. Unlike many fellow figurative painters, we are not exploring the artist’s autobiographical history, her relations, her emotions - we dive into a shared cultural heritage, the history of art, and moral codes, all applied to one's physical body, which she rarely depicts as a whole, choosing the detail instead.

Just like a journalist writes a text based on the transcription of an audio recording, González Martín researches the past, looking for elements and messages to recreate, discovering similarities between what was and what is, drawing a line that transcends space and connects us with another era. Naked female bodies and intimate details appear to live in a suspended timeline - how can we place them in a specific moment and time, with little to no clothes or accessories or architecture around them? But González Martín does not hide the origin of her research: welcome back to the Middle Ages. It is, in fact, the content we find in Medieval art, both religious and not, that allows the artist to explore women's bodies and their sexuality, a strong Catholic narrative, and the concepts of Saints and their accolades, without an overpowering linear narrative.

The subjects we admire are the result of a collage of real people, found in existing artworks, and ideal features that arise in González Martín’s mind during the research process. Sourcing from museums and churches of Brescia, Milan and Padua, we find ourselves before the result of cross-contamination, ultimately manifested by the rather rare use of thick wooden boards, borrowed by the formal qualities of icon paintings, and oil: the ultimate technique that throws us back into the origin of oil painting. There is no preparatory drawing behind the image drawn onto the solid material, the outcome of a virtual cropping and editing process that happens naturally to González Martín, supported by an endless archive of visual imagery accumulated over time. The artist creates in fact her own private collection of paintings, creating and recreating. At last, the wood element helps us perceive the artwork more as an object and draws us away from the classic idea of a painting, justifying the existence of the message sewn into the image. Yet we find ourselves in front of a contradiction: how can such an object be perceived as utilitarian?

At first glance we could compare González Martín's formal approach to the pictures with the concept of ‘horror vacui’: there is rarely an empty spot, all details are taken care of with absolute precision, we observe crammed crops of naked bodies that highlight a single message found within a larger message, yet we are left with room for interpretation. What lies around these details, how do we imagine the rest of the subject’s body? Nothing is left to chance, we observe portraits of emotions rather than portraits of people.

There is a tender intimacy in the small size of the works, which invites us to get closer to the image and explore its many details. Nudity is never vulgar nor sexy, but rather sensual and delicate. There is no room for distractions, we can focus on the pure essence of the body and its messages. Only sometimes González Martín decides to wink at us, carefully inserting some ghostly details that catapult the subjects into a contemporary context. For example, the soft tan mark of a bikini. But hey, did we not discover some frescoes with women in bikinis in a Roman domus, in Pompeii? Again, it’s hard to place the pictures in a specific timeline.

We should not consider the drawings as preparatory business, or unfinished projects. They have a life of their own, they are necessary in order to express quicker ideas and often the inspiration behind each of them comes from a different source. The coloured pencil on ivory paper helps manifest a looser, different kind of imagination.

The titles of the artworks come in bulk, at the end of each body of works: the glue that creates a story, a medium that gives another narrative without changing the pairing visually. The text, taken by literature writings and poetry, help us shine a new light onto the message.

González Martín takes us by hand and walks us through the forgotten painting section of our favourite museum, celebrating the past and present, allowing those who will live in the future to enjoy a glimpse of our most real and intimate memories.

Just like a journalist writes a text based on the transcription of an audio recording, González Martín researches the past, looking for elements and messages to recreate, discovering similarities between what was and what is, drawing a line that transcends space and connects us with another era. Naked female bodies and intimate details appear to live in a suspended timeline - how can we place them in a specific moment and time, with little to no clothes or accessories or architecture around them? But González Martín does not hide the origin of her research: welcome back to the Middle Ages. It is, in fact, the content we find in Medieval art, both religious and not, that allows the artist to explore women's bodies and their sexuality, a strong Catholic narrative, and the concepts of Saints and their accolades, without an overpowering linear narrative.

The subjects we admire are the result of a collage of real people, found in existing artworks, and ideal features that arise in González Martín’s mind during the research process. Sourcing from museums and churches of Brescia, Milan and Padua, we find ourselves before the result of cross-contamination, ultimately manifested by the rather rare use of thick wooden boards, borrowed by the formal qualities of icon paintings, and oil: the ultimate technique that throws us back into the origin of oil painting. There is no preparatory drawing behind the image drawn onto the solid material, the outcome of a virtual cropping and editing process that happens naturally to González Martín, supported by an endless archive of visual imagery accumulated over time. The artist creates in fact her own private collection of paintings, creating and recreating. At last, the wood element helps us perceive the artwork more as an object and draws us away from the classic idea of a painting, justifying the existence of the message sewn into the image. Yet we find ourselves in front of a contradiction: how can such an object be perceived as utilitarian?

At first glance we could compare González Martín's formal approach to the pictures with the concept of ‘horror vacui’: there is rarely an empty spot, all details are taken care of with absolute precision, we observe crammed crops of naked bodies that highlight a single message found within a larger message, yet we are left with room for interpretation. What lies around these details, how do we imagine the rest of the subject’s body? Nothing is left to chance, we observe portraits of emotions rather than portraits of people.

There is a tender intimacy in the small size of the works, which invites us to get closer to the image and explore its many details. Nudity is never vulgar nor sexy, but rather sensual and delicate. There is no room for distractions, we can focus on the pure essence of the body and its messages. Only sometimes González Martín decides to wink at us, carefully inserting some ghostly details that catapult the subjects into a contemporary context. For example, the soft tan mark of a bikini. But hey, did we not discover some frescoes with women in bikinis in a Roman domus, in Pompeii? Again, it’s hard to place the pictures in a specific timeline.

We should not consider the drawings as preparatory business, or unfinished projects. They have a life of their own, they are necessary in order to express quicker ideas and often the inspiration behind each of them comes from a different source. The coloured pencil on ivory paper helps manifest a looser, different kind of imagination.

The titles of the artworks come in bulk, at the end of each body of works: the glue that creates a story, a medium that gives another narrative without changing the pairing visually. The text, taken by literature writings and poetry, help us shine a new light onto the message.

González Martín takes us by hand and walks us through the forgotten painting section of our favourite museum, celebrating the past and present, allowing those who will live in the future to enjoy a glimpse of our most real and intimate memories.

20

maggio 2023

Fever of Happiness

Dal 20 maggio al 18 giugno 2023

arte contemporanea

Location

PALAZZO MONTI

Brescia, Piazza Tebaldo Brusato , 22, (Brescia)

Brescia, Piazza Tebaldo Brusato , 22, (Brescia)

Orario di apertura

Dal lunedì al sabato ore 10-18

Vernissage

20 Maggio 2023, Sabato 20 Maggio 2023 ore 18-21

Autore

Curatore

Autore testo critico