Create an account

Welcome! Register for an account

La password verrà inviata via email.

Recupero della password

Recupera la tua password

La password verrà inviata via email.

-

-

- Categorie

- #iorestoacasa

- Agenda

- Archeologia

- Architettura

- Arte antica

- Arte contemporanea

- Arte moderna

- Arti performative

- Attualità

- Bandi e concorsi

- Beni culturali

- Cinema

- Contest

- Danza

- Design

- Diritto

- Eventi

- Fiere e manifestazioni

- Film e serie tv

- Formazione

- Fotografia

- Libri ed editoria

- Mercato

- MIC Ministero della Cultura

- Moda

- Musei

- Musica

- Opening

- Personaggi

- Politica e opinioni

- Street Art

- Teatro

- Viaggi

- Categorie

-

Chiara Coccorese / Alessio Delfino

La doppia personale presso la Galleria Paolo Erbetta espone i recenti lavori di Alessio Delfino (1976 Savona) e Chiara Coccorese (1982 Napoli), due artisti che “giocano” con la fotografia in senso letterale e metaforico…

Comunicato stampa

Segnala l'evento

La doppia personale presso la Galleria Paolo Erbetta espone i recenti lavori di Alessio Delfino (1976 Savona) e Chiara Coccorese (1982 Napoli), due artisti che “giocano” con la fotografia in senso letterale e metaforico: “letterale” perché entrambi amano dedicare energie alla costruzione dei propri set; “metaforico” perché in questo gioco con la fotografia è la stessa fotografia ad essere messa in gioco nella sua natura di obiettiva riproduzione del reale e diventa proiezione dell'interiorità.

Tarots è la nuova serie fotografica di Alessio Delfino, dedicata alla rappresentazione dei ventidue arcani maggiori del mazzo del Tarocco Marsigliese, nella versione commissionata nella prima metà del XV secolo dal duca di Milano Filippo Maria Visconti che rappresenta la più alta espressione del tarocco nei secoli.

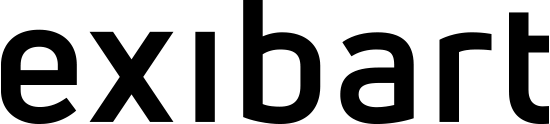

Nel suo lavoro ultradecennale il giovane fotografo savonese ha messo al centro del proprio lavoro la donna come oggetto di studio. Nei Tarots la forza del simbolo si intreccia al potere seduttivo del corpo. E' L'Imperatrice il primo scatto di questa ricerca “sapienziale” che interpreta i tarocchi in versione femminile. L'uomo è soggiogato al destino, così come lo è all'eterno femminino, che gli si sovrappone in un gioco di rimandi. Le Diable vede in scena un uomo assoggettato al potere muliebre. In una società laica e improntata dall'esaltazione del self made man, l'idea di destino non ha molto seguito. Compiendo un'operazione pop, Delfino trova il modo di parlare di quel “fato” che è per secoli ha rappresentato una vera ossessione culturale per l'uomo. Senza il Fato non esisterebbero infatti i poemi antichi, la tragedia greca, l'astrologia e molto altro, inclusi i Tarocchi. La femme fatale dei Tarots di Delfino ha origine da qui. Utilizzando lo stile neobarocco, la fotografia di Delfino parla di un mondo inteso come “grande rappresentazione” e della vita come un percorso di assoggettamento, più o meno volontario e consapevole, al potere del simbolico. Lo fa unendo alcuni punti di riferimento, da Erwin Olaf a Helmut Newton, passando per David LaChapelle. Se del primo, Delfino ammira le atmosfere vintage ed eleganti, evocative e misteriose, del secondo apprezza l'uso di modelle dotate di una bellezza post-femminista, più consapevole e dai tratti aggressivi, decisionisti, manageriali, perfino sadici. Dall'ultimo, Delfino desume invece un certo gusto per il gioco, per l'ammiccamento e per un barocchismo che, se in LaChapelle si conoscono i noti eccessi ultrapop e manieristi, in Delfino restano sommessi per non rompere l'equilibrio imposto dal serafico afflato delle carte del destino. Un flatus voci, quello de L'Imperatrice, che irrompe da una simbiosi postmoderna in cui la fotografia sfrutta ogni sua possibilità per creare uno spazio in cui i sensi e i simboli possono aleggiare con drammatica leggerezza, senza perdere la profondità di una sensazione originaria e senza piombare nei fasti desueti della retorica. Come fa notare Roland Barthes in un suo libro capitale, per chi guarda “è come se” dovesse “leggere nella Fotografia i miti del Fotografo, fraternizzando con loro, senza crederci troppo”. La fotografia di Delfino produce un tale effetto di fascinazione non violenta, di seduzione giocosa, di seria ilarità dando all'immagine la possibilità d'essere letta su più piani.

Nella precedente serie Femmes d'or, invece, Delfino matura una astrazione e drammatizzazione del nudo. Dopo aver dedicato due serie alla trasformazione del corpo in paesaggio e alla trasfigurazione della carne in esile scrittura di luce, Delfino approda ad una serie in cui usa la body painting dorata su modelle non professioniste, per offrire una diversa tessitura alla pelle ed impostare un altro rapporto tra carne, luce e fotografia. Intrappolati dentro spesse cornici dorate, figlie di un certo gusto barocco per l'eccesso, questi frammenti di corpi danzanti divengono oggetti voluttuosi e drammatici. La consistenza eterea delle masse, la plasticità dei volumi corporei e l'armonia delle forme determinano una fotografia scultorea, in cui il corpo assume una valenza spirituale. Il frammento corporeo permette di cogliere meglio l'espressività del tutto, tenendo a debita distanza l'erotismo, al quale Delfino pone rimedio “denudando il nudo”, togliendo ogni segno e cercando del corpo una forma più autentica, una vitalità più vera.

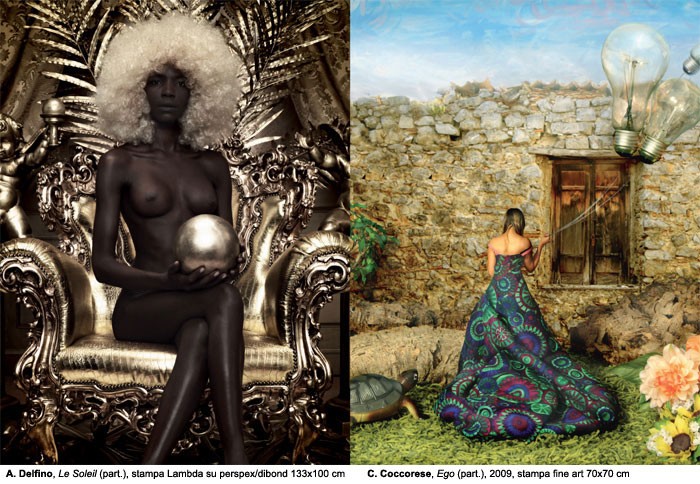

Se il mondo di Delfino è rivolto alle suggestioni provenienti da un mondo antico e scomparso che crede nella bellezza come armonia e nel destino come “libro” già scritto, quello di Chiara Coccorese è invece rivolto ad un altro luogo di sopravvivenza del “mito”. Si tratta di un luogo accogliente e inquietante quale è quello della fiaba. Grazie ad un approccio narrativo alla fotografia di genere stage photography, Coccorese ricostruisce un mondo utilizzando il linguaggio sognante dell'infanzia. Uno stadio dell'esistenza connotato da un approccio gnoseologico al gioco: costruendo il proprio universo si ripete quello reale al fine di renderlo familiare, giocandoci come se quel questo potesse essere disponibile, addomesticabile. L'ottica mitizzante serve proprio ad abbellire e personificare le “quattro stagioni”, ad esempio, al fine di creare un ponte antropologico con la Natura indifferente rispetto al destino e al dolore umani, di cui Giacomo Leopardi ha lasciato un testamento assoluto nel Dialogo della Natura e di un islandese.

In questa ricostruzione l'artista si chiama in causa attraverso un lavorio di specchi riflettenti la propria immagine. Aspetto concettuale di una fotografia che fornisce una visione surreale, divertita e divertente, ma cerca un contatto con gli aspetti più ideali del fotografare: l'autorialità, il rapporto tra il soggetto e l'oggetto del fotografare, la presenza dell'autore nell'opera. Come ci ha insegnato il capolavoro aurorale di Diego Velàzquez, Las Meninas, l'autore dell'opera può entrare a farne parte attraverso uno sguardo che renda evidente la propria autorevolezza. Coccorese lo fa in Autunno, dove inscena un personaggio femminile immerso dentro una scena di sapore autunnale. Il fondale è dipinto, gli alberi sono fatti di frutti e bacche, il terreno è popolato di foglie secche e noci la donna è fatta di legni. Tutto è finto perché sia vero. L'idea del pupazzo viene qui messa al centro di un gioco di cui l'autrice è il deus ex machina, la designer di una scenografia che possiede i caratteri di una narrazione che non porta in nessun luogo, come una favola appena accennata da leggere in profondità, come lo Spaventapasseri crocifisso, piuttosto che nella distensione cronologica. Ci si aspetta una storia, ma i lavori di Coccorese sono legati ad una visionarietà che apre una dimensione del narrare che collega le inquietudini del sogno e la semplicità della favola ad certo un simbolismo infantile. Coccorese illustra i capitoli di una narrazione che si dipana come un sogno, come una fiaba destrutturata, in cui i personaggi e i paesaggi non stanno più insieme ma vanno ciascuno per conto proprio. Un mondo di colori come ne la Fabbrica di cioccolato diretta da quel Tim Burton a cui Coccorese potrebbe essere debitrice, se soltanto il suo lavoro propendesse decisamente verso la direzione del grottesco invece di optare per una più genuina vena drammatica e giocosa che l'avvicina al teatro delle maschere italiano e che proprio nella tradizione partenopea sa essere così ricco di colori e personaggi.

La fotografia di Coccorese parte da dove Andy Warhol ha terminato e da quella consapevolezza che la stage photography ha maturato, confermando l'intenzione degli artisti di fotografare mondi da loro stessi creati. La fine dell'immagine “per eccesso di immagini” profetizzata da Warhol, che serigrafava foto “rubate” ai media, porta alla fine della fotografia pensata come racconto del reale e fa nascere un nuovo mondo che bene ha descritto un “fotografo giocoliere” come Vik Muniz, usando la massima: “Non c'è più nulla da fotografare. Se vuoi fotografare qualcosa di nuovo, devi prima crearlo”. E' la nascita di una fotografia che registra un mondo creato appositamente per lei, spesso per un solo battito del suo otturatore.

Nicola Davide Angerame

-----------------------------------------

The Paolo Erbetta Gallery presents a double personal exhibition of recent works by Alessio Delfino (1976 Savona) and Chiara Coccorese (1982 Naples), two artists who “play” with photography in both a literal and metaphorical sense: “literal” because both enjoy focusing energy on creating their own sets; “metaphorical” because when photography’s natural objective reproduction of reality is put up for discussion photography itself becomes a projection of interiority.

Tarots is the new photographic series by Alessio Delfino, dedicated to the twenty-two major arcana cards of the Marseilles tarot deck, in the version commissioned during the first half of the 15th century by the Duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti, that represents the highest expression of the tarot cards over the centuries.

In more than a decade of work, this young photographer from Savona has focused his artistic spotlight on the woman. In Tarots, the strength of the symbol is interwoven with the seductive power of the body. The L’Imperatrice is the first photograph of this “knowledgeable” search that interprets the tarot cards from a feminine perspective. Man is subjugated to destiny, as he is to the eternal feminine, that first relinquishes control and then takes it back in a seesawing interplay. In the Le Diable a man is subjugated to a woman’s power. In a laic society that exalts the self-made man, the concept of destiny does not have much of a following. Through a pop operation, Delfino finds a way to talk about that “fate” that for centuries represented a real cultural obsession for man. In point of fact, without Fate ancient poems, Greek tragedy, astrology and much more, including the Tarot cards, would not exist. This is the origin behind Delfino’s femme fatale of the Tarots. Through the Neo-Baroque style, Delfino’s photography talks about a world understood as a “great representation” and about life as a path of more or less voluntary and conscious subjugation to the power of the symbolic. This is done by linking some points of reference, including Erwin Olaf, Helmut Newton and David LaChapelle. If Delfino admires the first’s vintage, elegant, evocative and mysterious atmospheres, he appreciates the second one’s use of models with post-feminist beauty and heightened awareness, with aggressive, decisive, managerial and even sadistic features. For the last reference, Delfino infers instead an evident gusto for playing, mischievousness and a Baroque mannerism that if in LaChapelle are represented by the celebrated ultra-pop and mannerist excesses, in Delfino remain subdued to avoid upsetting the balance imposed by the seraphic inspiration of the cards of fate. A flatus voci, that of the L'Imperatrice, that bursts from a post-modern symbiosis in which photography exploits all its potential to create a space in which the senses and symbols waft with dramatic lightness, without losing the depth of an original feeling and without plunging into the outdated pomp of rhetoric. As pointed out by Roland Barthes in one of his fundamental books, for the observer “it is as if” photography “allows him to see the photographer’s legends, fraternizing with them but not quite believing in them”. Delfino’s photography produces exactly such an effect of non-violent fascination, of playful seduction, of serious hilarity, allowing the image to be interpreted at various levels.

Instead, in the previous series Femmes d’or, Delfino elaborates an abstraction and dramatization of the nude. After having dedicated two series to the transformation of the body into a landscape and to the transfiguration of the flesh into tenuous traces of light, Delfino ventures into a series in which he uses gold body painting on non-professional models to present a different texture of the skin and to establish another relationship between flesh, light and photography. Trapped inside thick gilded frames, the consequences of a certain Baroque taste for the extreme, these fragments of dancing bodies become voluptuous and dramatic objects. The ethereal consistency of the masses, the plasticity of the corporeal volumes and the harmony of the forms create sculptural photography, in which the body assumes a spiritual value. The corporeal fragment enhances the perception of the expressivity of the whole, keeping eroticism at a proper distance, a situation that Delfino remedies by “denuding the nude”, removing all symbolic references while seeking a more authentic form and a truer vitality for the body.

If Delfino’s world focuses on the ideas from an ancient and now vanished world that believes in beauty as harmony and in destiny as a “book” that has already been written, the world of Chiara Coccorese concentrates instead on another place in which the “myth” survives. This is the comfortable and disturbing world of fairy-tales. Through a stage photography-based narrative approach, Coccorese reconstructs a world using the dream-like language of infancy. This stage of existence is characterized by a gnoseological approach to play: a personal universe is constructed in which the real one is repeated over and over to make it more familiar, playing within it as if it could be available, and tamable. The mythicizing focus is needed to embellish and personify the “four seasons”, for example, in order to create an anthropological link with nature, indifferent to destiny and to human suffering, and of which Giacomo Leopardi left an absolute legacy in his Dialog between Nature and an Icelander.

In this reconstruction, the artist gets involved through a flurry of activity with mirrors that reflect her image. A conceptual aspect of photography that provides a surreal vision, that is amused and fun, but that seeks contact with the more ideal aspects of taking pictures: authoriality, the relationship between the subject and the subject being photographed and the presence of the artist in the work. As we learned from Diego Velàzquez’s auroral masterpiece, Las Meninas, the artist can become part of a work through a gaze that makes the artist’s authoritativeness evident. Coccorese does this in Autunno (Autumn), in which she represents a female character immersed in an autumn-like scene. The backdrop is painted, the trees are made of fruits and berries, the soil is covered with dry leaves and walnuts, and the woman is made out of wood. Everything is fake so that it is real. Here, the idea of the puppet is put on center stage in a game for which the artist is the dues ex machina, the designer of scenery with the characteristics of a narration that take us nowhere, like a fairy-tale that is partially spun and should be read between the lines, such as the crucified Scarecrow, rather than to be taken for what it is. We expect a story, but the works by Coccorese are connected to a visionary concept that opens a dimension of narration that links the apprehension of a dream and the simplicity of the fairy-tale to a certain infantile symbolism. Coccorese illustrates the chapters of a story that unravels like a dream, like a destructured fable, in which the characters and landscapes no longer stay together but each goes its own way. A world of colors like in The Chocolate Factory, directed by that Tim Burton to whom Coccorese might have drawn on for inspiration if her work had leaned decidedly toward the grotesque instead of toward a more genuine dramatic and playful mood that brings it closer to the theater of the Italian masks that, in the authentic Neapolitan tradition, is teeming with colors and characters.

Coccorese’s photography starts from where Andy Warhol ended and from that awareness that stage photography has developed, confirming the intention of artists to photograph worlds that they themselves have created. The end of the image “caused by too many images” as predicted by Warhol, who silk-screened photographs “stolen” from the mass media, leads to the end of photography conceived as a tale of what is real and to the birth of a new world described so nicely by a “photographer juggler” like Vik Muniz, through the saying: “There is nothing more to photograph. If you want to photograph something new, you first have to create it”. It is the birth of a photography that records a world created especially for it, often for just one click of the shutter.

Nicola Davide Angerame

Tarots è la nuova serie fotografica di Alessio Delfino, dedicata alla rappresentazione dei ventidue arcani maggiori del mazzo del Tarocco Marsigliese, nella versione commissionata nella prima metà del XV secolo dal duca di Milano Filippo Maria Visconti che rappresenta la più alta espressione del tarocco nei secoli.

Nel suo lavoro ultradecennale il giovane fotografo savonese ha messo al centro del proprio lavoro la donna come oggetto di studio. Nei Tarots la forza del simbolo si intreccia al potere seduttivo del corpo. E' L'Imperatrice il primo scatto di questa ricerca “sapienziale” che interpreta i tarocchi in versione femminile. L'uomo è soggiogato al destino, così come lo è all'eterno femminino, che gli si sovrappone in un gioco di rimandi. Le Diable vede in scena un uomo assoggettato al potere muliebre. In una società laica e improntata dall'esaltazione del self made man, l'idea di destino non ha molto seguito. Compiendo un'operazione pop, Delfino trova il modo di parlare di quel “fato” che è per secoli ha rappresentato una vera ossessione culturale per l'uomo. Senza il Fato non esisterebbero infatti i poemi antichi, la tragedia greca, l'astrologia e molto altro, inclusi i Tarocchi. La femme fatale dei Tarots di Delfino ha origine da qui. Utilizzando lo stile neobarocco, la fotografia di Delfino parla di un mondo inteso come “grande rappresentazione” e della vita come un percorso di assoggettamento, più o meno volontario e consapevole, al potere del simbolico. Lo fa unendo alcuni punti di riferimento, da Erwin Olaf a Helmut Newton, passando per David LaChapelle. Se del primo, Delfino ammira le atmosfere vintage ed eleganti, evocative e misteriose, del secondo apprezza l'uso di modelle dotate di una bellezza post-femminista, più consapevole e dai tratti aggressivi, decisionisti, manageriali, perfino sadici. Dall'ultimo, Delfino desume invece un certo gusto per il gioco, per l'ammiccamento e per un barocchismo che, se in LaChapelle si conoscono i noti eccessi ultrapop e manieristi, in Delfino restano sommessi per non rompere l'equilibrio imposto dal serafico afflato delle carte del destino. Un flatus voci, quello de L'Imperatrice, che irrompe da una simbiosi postmoderna in cui la fotografia sfrutta ogni sua possibilità per creare uno spazio in cui i sensi e i simboli possono aleggiare con drammatica leggerezza, senza perdere la profondità di una sensazione originaria e senza piombare nei fasti desueti della retorica. Come fa notare Roland Barthes in un suo libro capitale, per chi guarda “è come se” dovesse “leggere nella Fotografia i miti del Fotografo, fraternizzando con loro, senza crederci troppo”. La fotografia di Delfino produce un tale effetto di fascinazione non violenta, di seduzione giocosa, di seria ilarità dando all'immagine la possibilità d'essere letta su più piani.

Nella precedente serie Femmes d'or, invece, Delfino matura una astrazione e drammatizzazione del nudo. Dopo aver dedicato due serie alla trasformazione del corpo in paesaggio e alla trasfigurazione della carne in esile scrittura di luce, Delfino approda ad una serie in cui usa la body painting dorata su modelle non professioniste, per offrire una diversa tessitura alla pelle ed impostare un altro rapporto tra carne, luce e fotografia. Intrappolati dentro spesse cornici dorate, figlie di un certo gusto barocco per l'eccesso, questi frammenti di corpi danzanti divengono oggetti voluttuosi e drammatici. La consistenza eterea delle masse, la plasticità dei volumi corporei e l'armonia delle forme determinano una fotografia scultorea, in cui il corpo assume una valenza spirituale. Il frammento corporeo permette di cogliere meglio l'espressività del tutto, tenendo a debita distanza l'erotismo, al quale Delfino pone rimedio “denudando il nudo”, togliendo ogni segno e cercando del corpo una forma più autentica, una vitalità più vera.

Se il mondo di Delfino è rivolto alle suggestioni provenienti da un mondo antico e scomparso che crede nella bellezza come armonia e nel destino come “libro” già scritto, quello di Chiara Coccorese è invece rivolto ad un altro luogo di sopravvivenza del “mito”. Si tratta di un luogo accogliente e inquietante quale è quello della fiaba. Grazie ad un approccio narrativo alla fotografia di genere stage photography, Coccorese ricostruisce un mondo utilizzando il linguaggio sognante dell'infanzia. Uno stadio dell'esistenza connotato da un approccio gnoseologico al gioco: costruendo il proprio universo si ripete quello reale al fine di renderlo familiare, giocandoci come se quel questo potesse essere disponibile, addomesticabile. L'ottica mitizzante serve proprio ad abbellire e personificare le “quattro stagioni”, ad esempio, al fine di creare un ponte antropologico con la Natura indifferente rispetto al destino e al dolore umani, di cui Giacomo Leopardi ha lasciato un testamento assoluto nel Dialogo della Natura e di un islandese.

In questa ricostruzione l'artista si chiama in causa attraverso un lavorio di specchi riflettenti la propria immagine. Aspetto concettuale di una fotografia che fornisce una visione surreale, divertita e divertente, ma cerca un contatto con gli aspetti più ideali del fotografare: l'autorialità, il rapporto tra il soggetto e l'oggetto del fotografare, la presenza dell'autore nell'opera. Come ci ha insegnato il capolavoro aurorale di Diego Velàzquez, Las Meninas, l'autore dell'opera può entrare a farne parte attraverso uno sguardo che renda evidente la propria autorevolezza. Coccorese lo fa in Autunno, dove inscena un personaggio femminile immerso dentro una scena di sapore autunnale. Il fondale è dipinto, gli alberi sono fatti di frutti e bacche, il terreno è popolato di foglie secche e noci la donna è fatta di legni. Tutto è finto perché sia vero. L'idea del pupazzo viene qui messa al centro di un gioco di cui l'autrice è il deus ex machina, la designer di una scenografia che possiede i caratteri di una narrazione che non porta in nessun luogo, come una favola appena accennata da leggere in profondità, come lo Spaventapasseri crocifisso, piuttosto che nella distensione cronologica. Ci si aspetta una storia, ma i lavori di Coccorese sono legati ad una visionarietà che apre una dimensione del narrare che collega le inquietudini del sogno e la semplicità della favola ad certo un simbolismo infantile. Coccorese illustra i capitoli di una narrazione che si dipana come un sogno, come una fiaba destrutturata, in cui i personaggi e i paesaggi non stanno più insieme ma vanno ciascuno per conto proprio. Un mondo di colori come ne la Fabbrica di cioccolato diretta da quel Tim Burton a cui Coccorese potrebbe essere debitrice, se soltanto il suo lavoro propendesse decisamente verso la direzione del grottesco invece di optare per una più genuina vena drammatica e giocosa che l'avvicina al teatro delle maschere italiano e che proprio nella tradizione partenopea sa essere così ricco di colori e personaggi.

La fotografia di Coccorese parte da dove Andy Warhol ha terminato e da quella consapevolezza che la stage photography ha maturato, confermando l'intenzione degli artisti di fotografare mondi da loro stessi creati. La fine dell'immagine “per eccesso di immagini” profetizzata da Warhol, che serigrafava foto “rubate” ai media, porta alla fine della fotografia pensata come racconto del reale e fa nascere un nuovo mondo che bene ha descritto un “fotografo giocoliere” come Vik Muniz, usando la massima: “Non c'è più nulla da fotografare. Se vuoi fotografare qualcosa di nuovo, devi prima crearlo”. E' la nascita di una fotografia che registra un mondo creato appositamente per lei, spesso per un solo battito del suo otturatore.

Nicola Davide Angerame

-----------------------------------------

The Paolo Erbetta Gallery presents a double personal exhibition of recent works by Alessio Delfino (1976 Savona) and Chiara Coccorese (1982 Naples), two artists who “play” with photography in both a literal and metaphorical sense: “literal” because both enjoy focusing energy on creating their own sets; “metaphorical” because when photography’s natural objective reproduction of reality is put up for discussion photography itself becomes a projection of interiority.

Tarots is the new photographic series by Alessio Delfino, dedicated to the twenty-two major arcana cards of the Marseilles tarot deck, in the version commissioned during the first half of the 15th century by the Duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti, that represents the highest expression of the tarot cards over the centuries.

In more than a decade of work, this young photographer from Savona has focused his artistic spotlight on the woman. In Tarots, the strength of the symbol is interwoven with the seductive power of the body. The L’Imperatrice is the first photograph of this “knowledgeable” search that interprets the tarot cards from a feminine perspective. Man is subjugated to destiny, as he is to the eternal feminine, that first relinquishes control and then takes it back in a seesawing interplay. In the Le Diable a man is subjugated to a woman’s power. In a laic society that exalts the self-made man, the concept of destiny does not have much of a following. Through a pop operation, Delfino finds a way to talk about that “fate” that for centuries represented a real cultural obsession for man. In point of fact, without Fate ancient poems, Greek tragedy, astrology and much more, including the Tarot cards, would not exist. This is the origin behind Delfino’s femme fatale of the Tarots. Through the Neo-Baroque style, Delfino’s photography talks about a world understood as a “great representation” and about life as a path of more or less voluntary and conscious subjugation to the power of the symbolic. This is done by linking some points of reference, including Erwin Olaf, Helmut Newton and David LaChapelle. If Delfino admires the first’s vintage, elegant, evocative and mysterious atmospheres, he appreciates the second one’s use of models with post-feminist beauty and heightened awareness, with aggressive, decisive, managerial and even sadistic features. For the last reference, Delfino infers instead an evident gusto for playing, mischievousness and a Baroque mannerism that if in LaChapelle are represented by the celebrated ultra-pop and mannerist excesses, in Delfino remain subdued to avoid upsetting the balance imposed by the seraphic inspiration of the cards of fate. A flatus voci, that of the L'Imperatrice, that bursts from a post-modern symbiosis in which photography exploits all its potential to create a space in which the senses and symbols waft with dramatic lightness, without losing the depth of an original feeling and without plunging into the outdated pomp of rhetoric. As pointed out by Roland Barthes in one of his fundamental books, for the observer “it is as if” photography “allows him to see the photographer’s legends, fraternizing with them but not quite believing in them”. Delfino’s photography produces exactly such an effect of non-violent fascination, of playful seduction, of serious hilarity, allowing the image to be interpreted at various levels.

Instead, in the previous series Femmes d’or, Delfino elaborates an abstraction and dramatization of the nude. After having dedicated two series to the transformation of the body into a landscape and to the transfiguration of the flesh into tenuous traces of light, Delfino ventures into a series in which he uses gold body painting on non-professional models to present a different texture of the skin and to establish another relationship between flesh, light and photography. Trapped inside thick gilded frames, the consequences of a certain Baroque taste for the extreme, these fragments of dancing bodies become voluptuous and dramatic objects. The ethereal consistency of the masses, the plasticity of the corporeal volumes and the harmony of the forms create sculptural photography, in which the body assumes a spiritual value. The corporeal fragment enhances the perception of the expressivity of the whole, keeping eroticism at a proper distance, a situation that Delfino remedies by “denuding the nude”, removing all symbolic references while seeking a more authentic form and a truer vitality for the body.

If Delfino’s world focuses on the ideas from an ancient and now vanished world that believes in beauty as harmony and in destiny as a “book” that has already been written, the world of Chiara Coccorese concentrates instead on another place in which the “myth” survives. This is the comfortable and disturbing world of fairy-tales. Through a stage photography-based narrative approach, Coccorese reconstructs a world using the dream-like language of infancy. This stage of existence is characterized by a gnoseological approach to play: a personal universe is constructed in which the real one is repeated over and over to make it more familiar, playing within it as if it could be available, and tamable. The mythicizing focus is needed to embellish and personify the “four seasons”, for example, in order to create an anthropological link with nature, indifferent to destiny and to human suffering, and of which Giacomo Leopardi left an absolute legacy in his Dialog between Nature and an Icelander.

In this reconstruction, the artist gets involved through a flurry of activity with mirrors that reflect her image. A conceptual aspect of photography that provides a surreal vision, that is amused and fun, but that seeks contact with the more ideal aspects of taking pictures: authoriality, the relationship between the subject and the subject being photographed and the presence of the artist in the work. As we learned from Diego Velàzquez’s auroral masterpiece, Las Meninas, the artist can become part of a work through a gaze that makes the artist’s authoritativeness evident. Coccorese does this in Autunno (Autumn), in which she represents a female character immersed in an autumn-like scene. The backdrop is painted, the trees are made of fruits and berries, the soil is covered with dry leaves and walnuts, and the woman is made out of wood. Everything is fake so that it is real. Here, the idea of the puppet is put on center stage in a game for which the artist is the dues ex machina, the designer of scenery with the characteristics of a narration that take us nowhere, like a fairy-tale that is partially spun and should be read between the lines, such as the crucified Scarecrow, rather than to be taken for what it is. We expect a story, but the works by Coccorese are connected to a visionary concept that opens a dimension of narration that links the apprehension of a dream and the simplicity of the fairy-tale to a certain infantile symbolism. Coccorese illustrates the chapters of a story that unravels like a dream, like a destructured fable, in which the characters and landscapes no longer stay together but each goes its own way. A world of colors like in The Chocolate Factory, directed by that Tim Burton to whom Coccorese might have drawn on for inspiration if her work had leaned decidedly toward the grotesque instead of toward a more genuine dramatic and playful mood that brings it closer to the theater of the Italian masks that, in the authentic Neapolitan tradition, is teeming with colors and characters.

Coccorese’s photography starts from where Andy Warhol ended and from that awareness that stage photography has developed, confirming the intention of artists to photograph worlds that they themselves have created. The end of the image “caused by too many images” as predicted by Warhol, who silk-screened photographs “stolen” from the mass media, leads to the end of photography conceived as a tale of what is real and to the birth of a new world described so nicely by a “photographer juggler” like Vik Muniz, through the saying: “There is nothing more to photograph. If you want to photograph something new, you first have to create it”. It is the birth of a photography that records a world created especially for it, often for just one click of the shutter.

Nicola Davide Angerame

19

dicembre 2009

Chiara Coccorese / Alessio Delfino

Dal 19 dicembre 2009 al 28 febbraio 2010

fotografia

Location

PAOLO ERBETTA ARTE CONTEMPORANEA

Foggia, Via Iv Novembre, 2, (Foggia)

Foggia, Via Iv Novembre, 2, (Foggia)

Orario di apertura

Lunedì - Sabato 11,00 - 13,00 / 17,00 - 20,30. Merc. e Giov. su appuntamento

Vernissage

19 Dicembre 2009, ore 18.30

Autore

Curatore