Create an account

Welcome! Register for an account

La password verrà inviata via email.

Recupero della password

Recupera la tua password

La password verrà inviata via email.

-

- container colonna1

- Categorie

- #iorestoacasa

- Agenda

- Archeologia

- Architettura

- Arte antica

- Arte contemporanea

- Arte moderna

- Arti performative

- Attualità

- Bandi e concorsi

- Beni culturali

- Cinema

- Contest

- Danza

- Design

- Diritto

- Eventi

- Fiere e manifestazioni

- Film e serie tv

- Formazione

- Fotografia

- Libri ed editoria

- Mercato

- MIC Ministero della Cultura

- Moda

- Musei

- Musica

- Opening

- Personaggi

- Politica e opinioni

- Street Art

- Teatro

- Viaggi

- Categorie

- container colonna2

- container colonna1

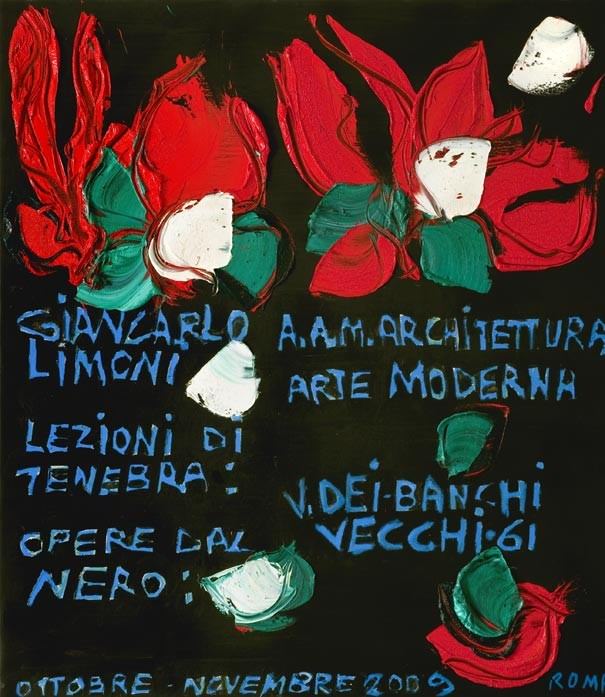

Giancarlo Limoni – Non ho tempo / Lezioni di tenebra: opere dal nero

L’artista presenta una ventina di opere di grande e medio formato degli ultimi due anni, all’insegna di un duplice tema. Il primo, “Non ho tempo” è un omaggio a È. Galois, fondatore dell’algebra astratta, il secondo dal titolo “Lezioni di tenebra” è invece un evidente riferimento a Roger Caillois.

Comunicato stampa

Segnala l'evento

Si inaugura Lunedì 19 Ottobre presso A.A.M. Architettura Arte Moderna una mostra dedicata a Giancarlo Limoni. A distanza di alcuni anni da una sua precedente personale tenuta presso la stessa A.A.M., l’artista presenta una ventina di opere recenti di grande e medio formato (olii su tela) risultato degli ultimi due anni di intenso e unitario lavoro, all’insegna di un duplice tema. Il primo, dal titolo “Non ho tempo” rappresenta una sorta di omaggio a Èvariste Galois, fondatore della moderna algebra astratta; romantico personaggio morto a soli vent’anni ed emblema di quanto troppo spesso la mediocrità trionfi sulla genialità, il cui lavoro, anche quello terminale redatto prima dell’alba del giorno del duello, durante terribili ore di disperazione, “costituisce ancora uno spunto di riflessione e di ricerca per i matematici moderni”. Il secondo tema dal titolo “Lezioni di tenebra: opere dal nero”, costituisce invece un evidente riferimento a Roger Caillois, straordinario scrittore e saggista, che ha segnato, fin dalle sue opere del 1938 la più attenta cultura internazionale e di cui vale la pena di ricordare almeno le superbe indicazioni a proposito del piacere dello scrivere in pura perdita come unico modo per scrivere liberamente (Il fiume Alfeo ‘78), cosi come la definizione della “ipertelia” quale sviluppo esagerato e sterile di alcuni organi, che porta all’esaurimento del senso a causa della crescita del segno. Ma le due anime del lavoro più sopra indicate trovano una loro straordinaria integrazione che deriva non tanto e non solo dall’essere tutte le opere uniformate dal fondo nero e bituminoso, da cui sembrano sollevarsi i grumi di pittura più accesi cromaticamente come scoppi improvvisi di luce e materia, quanto, piuttosto, dalla paziente e stratificata esecuzione delle opere stesse, quasi a scandire una successione temporale del lavoro che per successivi ispessimenti conduce all’epifania dell’opera stessa, a indicare che solo il tempo, l’intervallo, l’interruzione e poi la ripresa possono dar vita e senso ad un lavoro paziente e ostinato teso alla ricerca della propria stessa ragione di darsi e di offrirsi. Ma è un darsi inquietante quello che traspare da queste opere poiché immediata è la sensazione che tutte alludano alla possibilità di un prossimo e ravvicinato annullamento se non a un sottile equilibrio tra Eros e Thanatos come se dietro quelle lussureggianti e sontuose accensioni cromatiche si insinuasse prepotentemente l’idea della consunzione, l’idea della fine, l’idea della morte. Non è casuale che l’intero ciclo pittorico presentato in mostra cerchi una sorta di continuità con le radici della pittura più esistenziale, quella della seconda metà degli anni ’50 in cui più forte è avvertito l’equilibrio della tensione tra gli artisti il cui linguaggio si basava sull’emozione, sulla percezione di una possibile fine, sul disagio di vivere, legandosi a categorie espressive quali “segno”, “gesto” e “materia”. Ed è a questa precarietà esistenziale che Giancarlo Limoni sembra guardare durante l’evoluzione del proprio linguaggio poetico, quasi si fossero inseriti improvvisi e larvati timori in quel ritrovarsi di fronte a se stesso, senza giustificazioni consolatorie, senza finalità o teleologie ascrivibili a qualcosa o a qualcuno al di fuori di Sé. Un modo, quello dell’artista, di rivendicare la propria solitudine e quella del singolo individuo di fronte alle scelte fondamentali della propria esistenza, ma nello stesso tempo ribadendo la propria centralità quando si riascrive la possibilità a la responsabilità delle proprie scelte, alludendo così ad una propria contraddittoria collocazione tra vocazione “umanista” e condizione “individualista”. Non si può che essere soli, insieme ad altre solitudini, a rivendicare il proprio essere uomo a dispetto del buio percepito su una sempre più avvertita disgregazione se non fine dell’umanità stessa. Ma tutto ciò non significa affatto uno sguardo rivolto all’indietro da parte dell’artista, quanto piuttosto una precisa volontà di riannodare fili interrotti con una tradizione forse troppo in fretta consumata e liquidata, quasi a ricostruire un dialogo con quella pittura in cui il sentimento è sottile equilibrio tra opposte polarità come in Nicolas De Stael, cui G. Limoni sembra far riferimento, in quel suo riprendere l’idea di pittura al limite della dissoluzione, come unico modo per entrare in contatto con il mondo stesso, come se dipingere fosse un modo per manifestare la propria adesione al mondo stesso, ed esternare i propri desideri, con tesa partecipazione emotiva di cui ogni colpo di pennello è testimonianza, destinato a interrompersi bruscamente solo di fronte all’irrompere del tragico, dell’ignoto, dell’indecifrabile.

Le opere di G. Limoni, ci consegnano una straordinaria e costante applicazione nella volontà di penetrare nel colore, un intenso interesse cromatico stabilito su una base di tonalità raggianti nelle rapide pennellate dell’artista, così come sono costanti le sue attenzioni nell'osservazione della natura eternamente soggetto delle sue ricerche. Ma la natura per Limoni è anche la continua evocazione di una profondità raggiunta senza dispersioni e senza apprensioni apparenti; anche se l'inquietudine è presente dietro i fiori e rappresenta, in ogni modo, un’appartata, una nascosta qualità dell'artista. La vorticosità del segno in molte opere rappresenta la confidenza di Giancarlo Limoni con i propri strumenti, dimestichezza con i mezzi dell’arte sempre perseguiti. Con queste certezze/necessità gli spazi delle tele di Limoni si sono disposti, secondo un criterio prima complesso e immaginario, in flussi lineari di sostanza cromatica, poi si sono convertiti in mura di colore spesse e sontuose. Una simile evoluzione di ispessimento della vacuità, di condensamento del campo, limita i confini esterni delle figure fino a farle coincidere con esse. Il segno dell’artista diviene più inconsistente, meno animoso, l’esito è una giovinezza del tratto che diventa più accondiscendente, una spontaneità più tranquilla, una sicurezza quindi che viene sentita come anima di una coscienza, di una nuova capacità di emozionarsi artisticamente. Certo i lavori più recenti dell’artista hanno subito una sorta di “coup de fouet“ un vero colpo di frusta. Permane anche in questa fase del lavoro la fissazione-ossesione per il tutto pieno come se un sipario o comunque una siepe ci costringessero a permanere con lo sguardo sull’opera per scoprire sempre ulteriori dettagli in una sorta di caleidoscopico blow up. Ma questo evidenziato horror et amor vacui cede ora ad alcuni momenti di più diluita rarefazione: un vento barocco scompiglia come l’angelo di Benjamin qualsiasi tentativo di fissità. Se fino alla fine del millennio il permanere nelle opere di G. Limoni di alti orizzonti, di intravisti paesaggi che si facevano barriera tra cui comunque spuntava qualche sia pur parziale indicazione di “fondi“, alludeva ad una ricercata sospensione del tempo, in una sorta di limbo, ora, sempre più frequenti deflagrazioni e vorticose dinamicizzazioni alludono ad una precisa volontà di espressionistica deformazione del tutto. Si insinua uno scompigliamento barocco ad aprire veri e propri “golfi mistici” con veloci gestualità nell’estensione della materia pittorica che crea con la sua furia dapprima leggere increspature della superficie per poi giungere ad effervescenze di eruzioni magmatiche. Pure larve affioranti dal fondo sembrano indicare la strada più affine all’attuale ricerca di G. Limoni in cui il far pittura con l’alternanza di densità e di diluizione della materia riconduce l’opera nella condizione di fulminante e sfuggente pura apparizione.

Giancarlo Limoni è tra i protagonisti della Nuova Scuola Romana degli anni ’80, che vede negli stessi anni all’opera autori, tra gli altri, quali Bruno Ceccobelli, Gianni Dessì, Giuseppe Gallo, Enrico Luzzi, Nunzio, Claudio Palmieri, Piero Pizzi Cannella, Marco Tirelli, di cui alcuni avranno come riferimento la Galleria l'Attico di Fabio Sargentini.

Partecipa ad alcune tra le più importanti collettive di quegli anni: "Nuove trame dell'Arte" a Genazzano, "Anni ‘80" a Bologna, "La nuova scuola romana" a Graz, "Trent'anni dell'Attico" a Spoleto, "Capodopera" a Fiesole e "Post-Astrazione" a Milano. Dal 1986 ha trasferito il suo studio al quartiere Prenestino. Vive e lavora a Roma.

Monday 19th October, at A.A.M. Architettura Arte Moderna, sees the inauguration of an exhibition dedicated to Giancarlo Limoni. A few years on from his previous one-man show at the same gallery, the artist presents approximately twenty recent works in large and medium formats (oils on canvas) which represent the result of the last two years of intense and cohesive work under the heading of twin themes. The first, entitled “Non ho tempo” [“I haven't got time”] presents a sort of homage to Evariste Galois, founder of modern abstract algebra; a romantic figure who died at only twenty years of age and an emblem of how all too often mediocrity triumphs over genius. His work, even his very last which was written in the terrible hours of desperation before dawn on the day of the duel, “still constitutes a stimulus for reflection and research for modern mathematicians”. Whilst the second theme with the title “Lezioni di tenebra: opere dal nero” [“Lessons of darkness: works from black”], clearly refers to Roger Caillois the extraordinary writer and essayist who, with his works from 1938 onwards, left his mark on international culture at its most refined, and of whom it is worth remembering, at the very least, his superb suggestions regarding the pleasures of automatic writing as the only truly free method for writing (Le fleuve Alphée , 1978), along with his definition of “hypertelia” - the exaggerated and sterile development of certain organs – leading to the loss of meaning thanks to the over-development of the sign. But the dual spirits which, as we mentioned above, guide Limoni's work here, do reach an extraordinary degree of integration. This derives not so much and not only from the fact of the pieces having in common a black and bituminous ground, from which lumps of brighter paint seem to rise like sudden explosions of light and material, as, rather, from the patient and layered execution of the works themselves, which seems to measure out the work's progression over time, leading, through successive thickenings to an epiphany, and suggesting that only time, intervals, interruptions and then reprises can give life and sense to a patient and obstinate labour aimed at searching for the work's own reason for giving and for proffering of itself. But the offering that transpires in these pieces is disturbing because there is a very direct sensation that they all allude to the possibility of an imminent annulment, a closing-in, if not to a subtle equilibrium between Eros and Thanatos, as if behind those luxurious and sumptuous flashes of colour a domineering idea of consumption insinuates itself, the idea of an ending, of a death. It is no coincidence that the entire series of paintings presented in the exhibition seeks a sort of continuity with the roots of the painting of the most existential of periods, that of the late 1950s, in which there is a very strongly felt equilibrium in the tension among artists whose language was based on emotion, on the sense of a possible ending, on the difficulty of living, connected with expressive categories such as “sign”, “gesture” and “material”. And is it this existential precariousness that Giancarlo Limoni seems to be considering whilst his own poetic language evolves, almost as though sudden, disguised fears had slipped into that moment of self-confrontation, without any consoling explanations, without purposes or teleology that can be ascribed to anything or anyone apart from the Self. Thus the artist professes his own solitude and that of any individual facing the choices fundamental to his own existence, but at the same time he reiterates his own centrality when he reclaims the possibility of and the responsibility for his own decisions, in this way alluding to his own, contradictory, collocation somewhere between “humanist” vocation and “individualist” condition. We cannot but be alone - alongside other solitudes – as we defend our own essence as men, despite the darkness that seems to hover over an ever-more acute sense of the dissolution, if not the end, of humanity itself. This does not, however, mean that the artist is looking backwards, but, rather, that there is a clear desire to reunite the broken threads of a tradition that has been perhaps too soon consumed and liquidated, a desire almost to reconstruct a dialogue with that painting in which the sentiment is a subtle equilibrium between polar opposites, as in Nicolas De Stael, to whom Limoni seems to refer with his return to an idea of painting that borders on disintegration, as the only possible way of entering into contact with the world itself, as if the act of painting were a way of manifesting his own connection with the world, of expressing his own desires, with a tense emotional participation to which every stroke of the brush bears witness, destined to come to an abrupt halt only when faced with the sudden entrance of the tragic, of the unknown, of the indecipherable.

Limoni's works present us with an extraordinary and constant application in their desire to penetrate into colour, an intense chromatic interest based on radiant tonalities in the artist's rapid brush strokes, and the same constancy is to be seen in the attentive observations of nature that have always been one subject of his research. But nature, for Limoni, is also the continual evocation of a depth reached without dispersions and without apparent apprehensions; even if anxiety does lurk behind the flowers and represents, in any case, an aloof or hidden quality in the artist. The whirling signs in many of the works represent Giancarlo Limoni's confident relationship with his own tools, his skill with the means of expression that he has always pursued. With these certainties/necessities, the spaces of Limoni's canvases are arranged, initially according to a criterion that is complex and imaginary, in flowing lines of chromatic substance, then converted into walls of thick and sumptuous colours. A similar evolution, a thickening of the emptiness, a condensing of the field of colour, borders the external edges of the figures until they coincide. The artist's sign becomes more inconsistent, less bold, and the result is a youthfulness to the lines that become more obliging, a serener spontaneity, a self-assurance, therefore, which feels like the spirit of an awareness, of a new capacity, as an artist, to feel emotion. Certainly the artist's more recent work has experienced a sort of “coup de fouet”, a real fillip. In this phase of his work there also lingers the fixation/obsession with the filled space as though a curtain or at any rate a hedge were forcing our gaze to linger on the work in order to reveal ever more detail in a kind of kaleidoscopic blow up. But this very obvious horror et amor vacui now begins to make way for a few moments of more diluted rarefaction: a baroque wind, like Benjamin's angel, ruffles any attempt at fixity. Right up to the end of the millennium, in Limoni's works there used to linger high horizons, glimpses of landscape that acted as barriers through which, however, there peeped occasional, if partial, hints of “backgrounds”, and even if this alluded to a deliberate suspension of time, in a sort of limbo, nowadays increasingly frequent flare-ups and whirling dynamics suggest a specific desire for an expressionist deformation of the whole. A baroque disorder insinuates itself, opening up veritable “mystic gulfs” with the rapid gestures that apply the pictorial material, its fury at first creating gentle ruffles on the surface and then bubbling like erupting lava. Pure ghosts surfacing from the background seem to indicate the fittest route for Limoni's current research, in which the act of painting with the alternation of dense and diluted material leads his work back towards a condition of pure apparition that is both explosive and fugitive.

Giancarlo Limoni was one of the protagonists of the Nuova Scuola Romana (New Roman School) during the 1980s, alongside Bruno Ceccobelli, Gianni Dessì, Giuseppe Gallo, Enrico Luzzi, Nunzio, Claudio Palmieri, Piero Pizzi Cannella and Marco Tirelli, many of whom worked with Fabio Sargentini's gallery, L'Attico.

He participated in many of the most important group shows of the period: “Nuove trame dell'Arte" at Genazzano, "Anni ‘80" in Bologna, "La nuova scuola romana" at Graz, "Trent'anni dell'Attico" in Spoleto, "Capodopera" in Fiesole and "Post-Astrazione" in Milan. In 1986 he moved his studio to Rome's Prenestino district. He lives and works in the city of Rome.

Le opere di G. Limoni, ci consegnano una straordinaria e costante applicazione nella volontà di penetrare nel colore, un intenso interesse cromatico stabilito su una base di tonalità raggianti nelle rapide pennellate dell’artista, così come sono costanti le sue attenzioni nell'osservazione della natura eternamente soggetto delle sue ricerche. Ma la natura per Limoni è anche la continua evocazione di una profondità raggiunta senza dispersioni e senza apprensioni apparenti; anche se l'inquietudine è presente dietro i fiori e rappresenta, in ogni modo, un’appartata, una nascosta qualità dell'artista. La vorticosità del segno in molte opere rappresenta la confidenza di Giancarlo Limoni con i propri strumenti, dimestichezza con i mezzi dell’arte sempre perseguiti. Con queste certezze/necessità gli spazi delle tele di Limoni si sono disposti, secondo un criterio prima complesso e immaginario, in flussi lineari di sostanza cromatica, poi si sono convertiti in mura di colore spesse e sontuose. Una simile evoluzione di ispessimento della vacuità, di condensamento del campo, limita i confini esterni delle figure fino a farle coincidere con esse. Il segno dell’artista diviene più inconsistente, meno animoso, l’esito è una giovinezza del tratto che diventa più accondiscendente, una spontaneità più tranquilla, una sicurezza quindi che viene sentita come anima di una coscienza, di una nuova capacità di emozionarsi artisticamente. Certo i lavori più recenti dell’artista hanno subito una sorta di “coup de fouet“ un vero colpo di frusta. Permane anche in questa fase del lavoro la fissazione-ossesione per il tutto pieno come se un sipario o comunque una siepe ci costringessero a permanere con lo sguardo sull’opera per scoprire sempre ulteriori dettagli in una sorta di caleidoscopico blow up. Ma questo evidenziato horror et amor vacui cede ora ad alcuni momenti di più diluita rarefazione: un vento barocco scompiglia come l’angelo di Benjamin qualsiasi tentativo di fissità. Se fino alla fine del millennio il permanere nelle opere di G. Limoni di alti orizzonti, di intravisti paesaggi che si facevano barriera tra cui comunque spuntava qualche sia pur parziale indicazione di “fondi“, alludeva ad una ricercata sospensione del tempo, in una sorta di limbo, ora, sempre più frequenti deflagrazioni e vorticose dinamicizzazioni alludono ad una precisa volontà di espressionistica deformazione del tutto. Si insinua uno scompigliamento barocco ad aprire veri e propri “golfi mistici” con veloci gestualità nell’estensione della materia pittorica che crea con la sua furia dapprima leggere increspature della superficie per poi giungere ad effervescenze di eruzioni magmatiche. Pure larve affioranti dal fondo sembrano indicare la strada più affine all’attuale ricerca di G. Limoni in cui il far pittura con l’alternanza di densità e di diluizione della materia riconduce l’opera nella condizione di fulminante e sfuggente pura apparizione.

Giancarlo Limoni è tra i protagonisti della Nuova Scuola Romana degli anni ’80, che vede negli stessi anni all’opera autori, tra gli altri, quali Bruno Ceccobelli, Gianni Dessì, Giuseppe Gallo, Enrico Luzzi, Nunzio, Claudio Palmieri, Piero Pizzi Cannella, Marco Tirelli, di cui alcuni avranno come riferimento la Galleria l'Attico di Fabio Sargentini.

Partecipa ad alcune tra le più importanti collettive di quegli anni: "Nuove trame dell'Arte" a Genazzano, "Anni ‘80" a Bologna, "La nuova scuola romana" a Graz, "Trent'anni dell'Attico" a Spoleto, "Capodopera" a Fiesole e "Post-Astrazione" a Milano. Dal 1986 ha trasferito il suo studio al quartiere Prenestino. Vive e lavora a Roma.

Monday 19th October, at A.A.M. Architettura Arte Moderna, sees the inauguration of an exhibition dedicated to Giancarlo Limoni. A few years on from his previous one-man show at the same gallery, the artist presents approximately twenty recent works in large and medium formats (oils on canvas) which represent the result of the last two years of intense and cohesive work under the heading of twin themes. The first, entitled “Non ho tempo” [“I haven't got time”] presents a sort of homage to Evariste Galois, founder of modern abstract algebra; a romantic figure who died at only twenty years of age and an emblem of how all too often mediocrity triumphs over genius. His work, even his very last which was written in the terrible hours of desperation before dawn on the day of the duel, “still constitutes a stimulus for reflection and research for modern mathematicians”. Whilst the second theme with the title “Lezioni di tenebra: opere dal nero” [“Lessons of darkness: works from black”], clearly refers to Roger Caillois the extraordinary writer and essayist who, with his works from 1938 onwards, left his mark on international culture at its most refined, and of whom it is worth remembering, at the very least, his superb suggestions regarding the pleasures of automatic writing as the only truly free method for writing (Le fleuve Alphée , 1978), along with his definition of “hypertelia” - the exaggerated and sterile development of certain organs – leading to the loss of meaning thanks to the over-development of the sign. But the dual spirits which, as we mentioned above, guide Limoni's work here, do reach an extraordinary degree of integration. This derives not so much and not only from the fact of the pieces having in common a black and bituminous ground, from which lumps of brighter paint seem to rise like sudden explosions of light and material, as, rather, from the patient and layered execution of the works themselves, which seems to measure out the work's progression over time, leading, through successive thickenings to an epiphany, and suggesting that only time, intervals, interruptions and then reprises can give life and sense to a patient and obstinate labour aimed at searching for the work's own reason for giving and for proffering of itself. But the offering that transpires in these pieces is disturbing because there is a very direct sensation that they all allude to the possibility of an imminent annulment, a closing-in, if not to a subtle equilibrium between Eros and Thanatos, as if behind those luxurious and sumptuous flashes of colour a domineering idea of consumption insinuates itself, the idea of an ending, of a death. It is no coincidence that the entire series of paintings presented in the exhibition seeks a sort of continuity with the roots of the painting of the most existential of periods, that of the late 1950s, in which there is a very strongly felt equilibrium in the tension among artists whose language was based on emotion, on the sense of a possible ending, on the difficulty of living, connected with expressive categories such as “sign”, “gesture” and “material”. And is it this existential precariousness that Giancarlo Limoni seems to be considering whilst his own poetic language evolves, almost as though sudden, disguised fears had slipped into that moment of self-confrontation, without any consoling explanations, without purposes or teleology that can be ascribed to anything or anyone apart from the Self. Thus the artist professes his own solitude and that of any individual facing the choices fundamental to his own existence, but at the same time he reiterates his own centrality when he reclaims the possibility of and the responsibility for his own decisions, in this way alluding to his own, contradictory, collocation somewhere between “humanist” vocation and “individualist” condition. We cannot but be alone - alongside other solitudes – as we defend our own essence as men, despite the darkness that seems to hover over an ever-more acute sense of the dissolution, if not the end, of humanity itself. This does not, however, mean that the artist is looking backwards, but, rather, that there is a clear desire to reunite the broken threads of a tradition that has been perhaps too soon consumed and liquidated, a desire almost to reconstruct a dialogue with that painting in which the sentiment is a subtle equilibrium between polar opposites, as in Nicolas De Stael, to whom Limoni seems to refer with his return to an idea of painting that borders on disintegration, as the only possible way of entering into contact with the world itself, as if the act of painting were a way of manifesting his own connection with the world, of expressing his own desires, with a tense emotional participation to which every stroke of the brush bears witness, destined to come to an abrupt halt only when faced with the sudden entrance of the tragic, of the unknown, of the indecipherable.

Limoni's works present us with an extraordinary and constant application in their desire to penetrate into colour, an intense chromatic interest based on radiant tonalities in the artist's rapid brush strokes, and the same constancy is to be seen in the attentive observations of nature that have always been one subject of his research. But nature, for Limoni, is also the continual evocation of a depth reached without dispersions and without apparent apprehensions; even if anxiety does lurk behind the flowers and represents, in any case, an aloof or hidden quality in the artist. The whirling signs in many of the works represent Giancarlo Limoni's confident relationship with his own tools, his skill with the means of expression that he has always pursued. With these certainties/necessities, the spaces of Limoni's canvases are arranged, initially according to a criterion that is complex and imaginary, in flowing lines of chromatic substance, then converted into walls of thick and sumptuous colours. A similar evolution, a thickening of the emptiness, a condensing of the field of colour, borders the external edges of the figures until they coincide. The artist's sign becomes more inconsistent, less bold, and the result is a youthfulness to the lines that become more obliging, a serener spontaneity, a self-assurance, therefore, which feels like the spirit of an awareness, of a new capacity, as an artist, to feel emotion. Certainly the artist's more recent work has experienced a sort of “coup de fouet”, a real fillip. In this phase of his work there also lingers the fixation/obsession with the filled space as though a curtain or at any rate a hedge were forcing our gaze to linger on the work in order to reveal ever more detail in a kind of kaleidoscopic blow up. But this very obvious horror et amor vacui now begins to make way for a few moments of more diluted rarefaction: a baroque wind, like Benjamin's angel, ruffles any attempt at fixity. Right up to the end of the millennium, in Limoni's works there used to linger high horizons, glimpses of landscape that acted as barriers through which, however, there peeped occasional, if partial, hints of “backgrounds”, and even if this alluded to a deliberate suspension of time, in a sort of limbo, nowadays increasingly frequent flare-ups and whirling dynamics suggest a specific desire for an expressionist deformation of the whole. A baroque disorder insinuates itself, opening up veritable “mystic gulfs” with the rapid gestures that apply the pictorial material, its fury at first creating gentle ruffles on the surface and then bubbling like erupting lava. Pure ghosts surfacing from the background seem to indicate the fittest route for Limoni's current research, in which the act of painting with the alternation of dense and diluted material leads his work back towards a condition of pure apparition that is both explosive and fugitive.

Giancarlo Limoni was one of the protagonists of the Nuova Scuola Romana (New Roman School) during the 1980s, alongside Bruno Ceccobelli, Gianni Dessì, Giuseppe Gallo, Enrico Luzzi, Nunzio, Claudio Palmieri, Piero Pizzi Cannella and Marco Tirelli, many of whom worked with Fabio Sargentini's gallery, L'Attico.

He participated in many of the most important group shows of the period: “Nuove trame dell'Arte" at Genazzano, "Anni ‘80" in Bologna, "La nuova scuola romana" at Graz, "Trent'anni dell'Attico" in Spoleto, "Capodopera" in Fiesole and "Post-Astrazione" in Milan. In 1986 he moved his studio to Rome's Prenestino district. He lives and works in the city of Rome.

19

ottobre 2009

Giancarlo Limoni – Non ho tempo / Lezioni di tenebra: opere dal nero

Dal 19 ottobre al 28 novembre 2009

arte contemporanea

Location

A.A.M. – ARCHITETTURA ARTE MODERNA

Roma, Via Dei Banchi Vecchi, 61, (Roma)

Roma, Via Dei Banchi Vecchi, 61, (Roma)

Orario di apertura

da Lunedì e Domenica ore 16.00-20.00

Vernissage

19 Ottobre 2009, ore 18.30

Autore

Curatore