Create an account

Welcome! Register for an account

La password verrà inviata via email.

Recupero della password

Recupera la tua password

La password verrà inviata via email.

-

- container colonna1

- Categorie

- #iorestoacasa

- Agenda

- Archeologia

- Architettura

- Arte antica

- Arte contemporanea

- Arte moderna

- Arti performative

- Attualità

- Bandi e concorsi

- Beni culturali

- Cinema

- Contest

- Danza

- Design

- Diritto

- Eventi

- Fiere e manifestazioni

- Film e serie tv

- Formazione

- Fotografia

- Libri ed editoria

- Mercato

- MIC Ministero della Cultura

- Moda

- Musei

- Musica

- Opening

- Personaggi

- Politica e opinioni

- Street Art

- Teatro

- Viaggi

- Categorie

- container colonna2

- container colonna1

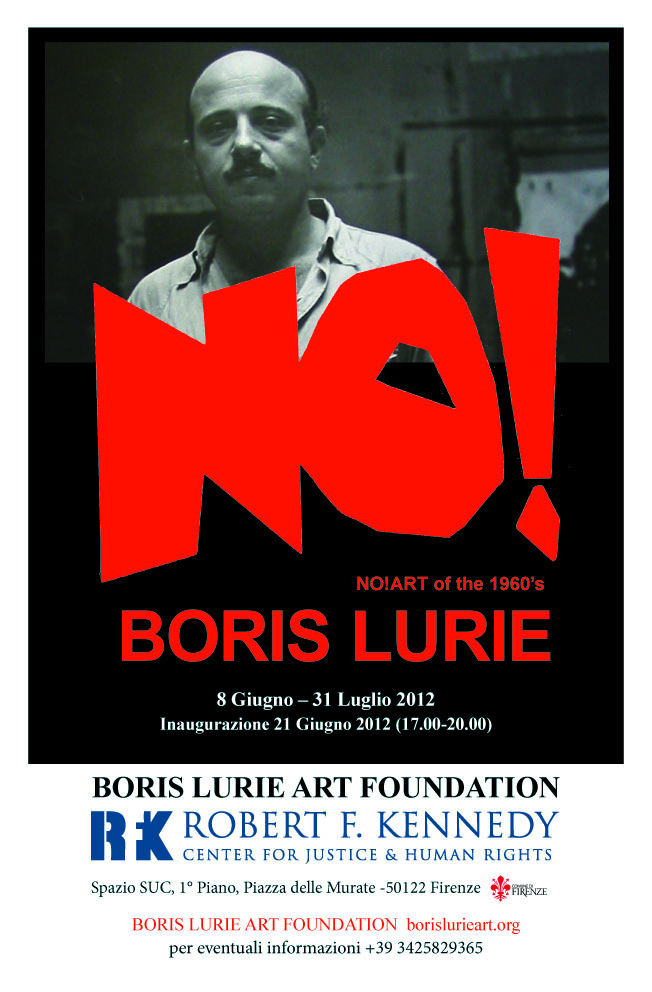

NO!ART of the 1960’s

“Lurie non permise mai che il mondo dimenticasse che, di fronte alle violazioni dei diritti umani, “NO!” è l’unica risposta accettabile.”

Comunicato stampa

Segnala l'evento

Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights (RFK) e Boris Lurie Art Foundation

presentano:

"NO!ART" of the 1960's

BORIS LURIE (1924 -2008)

Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights (RFK) in collaborazione con Boris Lurie Art Foundation è lieta di presentare "NO!ART" una mostra retrospettiva dell'artista Boris Lurie (1924 -2008) composta da 27 opere degli anni sessanta.

La mostra sarà aperta al pubblico dall’8 giugno al 31 luglio 2012 presso il Robert F. Kennedy Center di Firenze, nello Spazio SUC, al primo piano, in Piazza delle Murate.

Il ricevimento inaugurale si terrà invece successivamente, al RFK Center, giovedì 21 giugno 2012 alle ore 17.

Nella sua lettera di benvenuto alla mostra di Lurie, Kerry Kennedy, Presidente della Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights afferma:

“Nel corso di alcuni fra i decenni più tumultuosi della nostra storia, in anni in cui sono stati abbattuti e ricostruiti governi, e in cui la percezione culturale dei concetti di razza, etnicità, genere, e povertà è cambiata radicalmente, a causa di un mutamento globale di paradigma, Lurie non permise mai che il mondo dimenticasse che, di fronte alle violazioni dei diritti umani, “NO!” è l’unica risposta accettabile.”

Boris Lurie nacque a Leningrado nel 1924 e morì a New York nel 2008. La sua famiglia lasciò il paese tra la morte di Lenin e l'ascesa di Stalin, per stabilirsi a Riga, in Lettonia. Lurie frequentò le scuole di lingua tedesca fino a che i nazisti non lo rinchiusero nei lager con la sua famiglia. Dal 1941-1945, Lurie e suo padre vennero trasferiti in vari campi di concentramento, tra cui Stutthof e Buchenwald. Sua nonna, la madre e la sorella, vennero trucidate dai nazisti nel 1941 nell’eccidio di Rumbula, una zona balneare vicino Riga. L’esperienza di Lurie, internato da giovane nei campi di sterminio, segnerà profondamente la sua visione del mondo e la direzione che la sua arte avrebbe preso.

Dopo la loro liberazione, da parte delle truppe di Stalin, Lurie e suo padre vennero liberati ed emigrarono in America. Lurie aveva mostrato interesse per l'arte fin dalla tenera età e a New York lavorò per proprio, creando e sviluppandosi come artista. Fu proprio durante questo periodo Lurie che incontrò molti altri artisti, intellettuali, e persone a lui affini.

Sono passati oltre 50 anni dalla prima mostra italiana di Lurie presso la Galleria Arturo Schwarz a Milano. Fu una mostra condannata, osannata, discussa ma anche recensita, e divenne fondamentale per il movimento di avanguardia anti-establishment.

Al suo ritorno negli Stati Uniti, fu allestito il Doom Show alla March Gallery, sulle Decima strada Est di New York, il quartiere dei giovani artisti. In seguito Gertrude Stein portò la mostra in una galleria dei quartieri alti, nella zona degli artisti affermati.

John Wronoski ha scritto: "I soggetti di Lurie, implicitamente, erano sempre informati storicamente, socialmente e politicamente; ma nel 1959, quando fece amicizia con Sam Goodman e Stanley Fisher, il suo lavoro divenne più aggressivo intridendosi di critica sociale. Fondarono il Movimento NO! ART come reazione a tutto ciò che essi vedevano come il degrado dell’avanguardia, quale l'espressionismo astratto e il suo disimpegno politico e sociale, una resistenza che sarebbe diventata ancora più stridente con l'avvento della Pop Art.

NO! ART insisteva ancora una volta sul fatto che l'arte doveva affrontare il mondo reale. NO! ART chiamava a un'arte che avesse a che fare con le verità difficili, come l'imperialismo, il razzismo, la discriminazione sessuale, il consumismo, la proliferazione nucleare, portando all'azione sociale ".

The Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights

in conjunction with the Boris Lurie Art Foundation

present:

"NO!ART of the 1960's

BORIS LURIE (1924-2008)"

The Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights in conjunction with the Boris Lurie Art Foundation is proud to present a NO!ART exhibition of Boris Lurie’s art of the 1960’s. One June 21, the RFK Center’s Florence Office will host an opening reception for the exhibition, which includes a survey of Lurie’s work represented by 27 pieces.

In her welcome letter to the Boris Lurie exhibition, Kerry Kennedy, President of the

Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights states, “During some of the most tumultuous decades in our history—years that saw governments struck down and rebuilt, and in which cultural understandings of race, ethnicity, gender, and poverty were fundamentally re-shaped by global paradigm shifts—Lurie never let the world forget that when we see human rights violations in front of us, saying ‘NO!’ is the only acceptable answer.”

Lurie was born in Leningrad in 1924, and died in New York in 2008. His family fled the country after Lenin’s death and the rise of Stalin, settling in Riga, Latvia. Boris Lurie attended German-speaking schools until Nazis forced him and his family into concentration camps. From 1941-1945, Lurie and his father were moved to various concentration camps, including, Stutthof and Buchenwald. His grandmother, mother, and sister, were executed by the Nazis amid the 1941 massacre at Rumbula, a seaside district near Riga. Lurie’s experience as a young adult in the concentration camps deeply affected both his view of the world and the direction his art would take.

Subsequent to their liberation by Stalin’s troops, Lurie and his father were liberated and came to America. Lurie had shown an interest in art from an early age and in New York he worked on his own, creating and developing as an artist. It was during this time in New York that he met many other artists, intellectuals, and like-minded individuals.

Lurie had his inaugural show in Milan at the Arturo Schwarz Gallery more than 50 years ago. That show was condemned, praised, reviewed, and discussed, and it made an imprint on the avant-garde anti-establishment movement. Upon his return to New York, he organized the Doom Show at the March Gallery, located in a neighborhood filled with young artists new to the city. Gertrude Stein then moved the exhibition to a gallery uptown, which was considered the established artist section.

John Wronoski, Curator of Lurie’s exhibition in Boston, MA, writes, “Lurie’s subjects were always implicitly historically, socially, and politically informed, but in 1959, when he befriended Sam Goodman and Stanley Fisher, his work became more aggressive and would be infused with social criticism. They founded the NO!ART movement as a reaction against what they viewed as the debased avant-garde of Abstract Expressionism and its social and political dis-engagement, a resistance that would become all the more strident with the rise of Pop Art. NO!ART insisted that art again address the real world. NO!ART called for an art dealing with difficult truths, such as imperialism, racism, sexism, consumerism, and nuclear proliferation, and leading to social action.”

presentano:

"NO!ART" of the 1960's

BORIS LURIE (1924 -2008)

Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights (RFK) in collaborazione con Boris Lurie Art Foundation è lieta di presentare "NO!ART" una mostra retrospettiva dell'artista Boris Lurie (1924 -2008) composta da 27 opere degli anni sessanta.

La mostra sarà aperta al pubblico dall’8 giugno al 31 luglio 2012 presso il Robert F. Kennedy Center di Firenze, nello Spazio SUC, al primo piano, in Piazza delle Murate.

Il ricevimento inaugurale si terrà invece successivamente, al RFK Center, giovedì 21 giugno 2012 alle ore 17.

Nella sua lettera di benvenuto alla mostra di Lurie, Kerry Kennedy, Presidente della Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights afferma:

“Nel corso di alcuni fra i decenni più tumultuosi della nostra storia, in anni in cui sono stati abbattuti e ricostruiti governi, e in cui la percezione culturale dei concetti di razza, etnicità, genere, e povertà è cambiata radicalmente, a causa di un mutamento globale di paradigma, Lurie non permise mai che il mondo dimenticasse che, di fronte alle violazioni dei diritti umani, “NO!” è l’unica risposta accettabile.”

Boris Lurie nacque a Leningrado nel 1924 e morì a New York nel 2008. La sua famiglia lasciò il paese tra la morte di Lenin e l'ascesa di Stalin, per stabilirsi a Riga, in Lettonia. Lurie frequentò le scuole di lingua tedesca fino a che i nazisti non lo rinchiusero nei lager con la sua famiglia. Dal 1941-1945, Lurie e suo padre vennero trasferiti in vari campi di concentramento, tra cui Stutthof e Buchenwald. Sua nonna, la madre e la sorella, vennero trucidate dai nazisti nel 1941 nell’eccidio di Rumbula, una zona balneare vicino Riga. L’esperienza di Lurie, internato da giovane nei campi di sterminio, segnerà profondamente la sua visione del mondo e la direzione che la sua arte avrebbe preso.

Dopo la loro liberazione, da parte delle truppe di Stalin, Lurie e suo padre vennero liberati ed emigrarono in America. Lurie aveva mostrato interesse per l'arte fin dalla tenera età e a New York lavorò per proprio, creando e sviluppandosi come artista. Fu proprio durante questo periodo Lurie che incontrò molti altri artisti, intellettuali, e persone a lui affini.

Sono passati oltre 50 anni dalla prima mostra italiana di Lurie presso la Galleria Arturo Schwarz a Milano. Fu una mostra condannata, osannata, discussa ma anche recensita, e divenne fondamentale per il movimento di avanguardia anti-establishment.

Al suo ritorno negli Stati Uniti, fu allestito il Doom Show alla March Gallery, sulle Decima strada Est di New York, il quartiere dei giovani artisti. In seguito Gertrude Stein portò la mostra in una galleria dei quartieri alti, nella zona degli artisti affermati.

John Wronoski ha scritto: "I soggetti di Lurie, implicitamente, erano sempre informati storicamente, socialmente e politicamente; ma nel 1959, quando fece amicizia con Sam Goodman e Stanley Fisher, il suo lavoro divenne più aggressivo intridendosi di critica sociale. Fondarono il Movimento NO! ART come reazione a tutto ciò che essi vedevano come il degrado dell’avanguardia, quale l'espressionismo astratto e il suo disimpegno politico e sociale, una resistenza che sarebbe diventata ancora più stridente con l'avvento della Pop Art.

NO! ART insisteva ancora una volta sul fatto che l'arte doveva affrontare il mondo reale. NO! ART chiamava a un'arte che avesse a che fare con le verità difficili, come l'imperialismo, il razzismo, la discriminazione sessuale, il consumismo, la proliferazione nucleare, portando all'azione sociale ".

The Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights

in conjunction with the Boris Lurie Art Foundation

present:

"NO!ART of the 1960's

BORIS LURIE (1924-2008)"

The Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights in conjunction with the Boris Lurie Art Foundation is proud to present a NO!ART exhibition of Boris Lurie’s art of the 1960’s. One June 21, the RFK Center’s Florence Office will host an opening reception for the exhibition, which includes a survey of Lurie’s work represented by 27 pieces.

In her welcome letter to the Boris Lurie exhibition, Kerry Kennedy, President of the

Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice & Human Rights states, “During some of the most tumultuous decades in our history—years that saw governments struck down and rebuilt, and in which cultural understandings of race, ethnicity, gender, and poverty were fundamentally re-shaped by global paradigm shifts—Lurie never let the world forget that when we see human rights violations in front of us, saying ‘NO!’ is the only acceptable answer.”

Lurie was born in Leningrad in 1924, and died in New York in 2008. His family fled the country after Lenin’s death and the rise of Stalin, settling in Riga, Latvia. Boris Lurie attended German-speaking schools until Nazis forced him and his family into concentration camps. From 1941-1945, Lurie and his father were moved to various concentration camps, including, Stutthof and Buchenwald. His grandmother, mother, and sister, were executed by the Nazis amid the 1941 massacre at Rumbula, a seaside district near Riga. Lurie’s experience as a young adult in the concentration camps deeply affected both his view of the world and the direction his art would take.

Subsequent to their liberation by Stalin’s troops, Lurie and his father were liberated and came to America. Lurie had shown an interest in art from an early age and in New York he worked on his own, creating and developing as an artist. It was during this time in New York that he met many other artists, intellectuals, and like-minded individuals.

Lurie had his inaugural show in Milan at the Arturo Schwarz Gallery more than 50 years ago. That show was condemned, praised, reviewed, and discussed, and it made an imprint on the avant-garde anti-establishment movement. Upon his return to New York, he organized the Doom Show at the March Gallery, located in a neighborhood filled with young artists new to the city. Gertrude Stein then moved the exhibition to a gallery uptown, which was considered the established artist section.

John Wronoski, Curator of Lurie’s exhibition in Boston, MA, writes, “Lurie’s subjects were always implicitly historically, socially, and politically informed, but in 1959, when he befriended Sam Goodman and Stanley Fisher, his work became more aggressive and would be infused with social criticism. They founded the NO!ART movement as a reaction against what they viewed as the debased avant-garde of Abstract Expressionism and its social and political dis-engagement, a resistance that would become all the more strident with the rise of Pop Art. NO!ART insisted that art again address the real world. NO!ART called for an art dealing with difficult truths, such as imperialism, racism, sexism, consumerism, and nuclear proliferation, and leading to social action.”

21

giugno 2012

NO!ART of the 1960’s

Dal 21 giugno al 31 luglio 2012

arte contemporanea

Location

ROBERT F. KENNEDY HUMAN RIGHTS EUROPE

Firenze, Via Ghibellina, 12A, (Firenze)

Firenze, Via Ghibellina, 12A, (Firenze)

Orario di apertura

tutti i giorni ore 12-00

Vernissage

21 Giugno 2012, h 17.00

Autore