Create an account

Welcome! Register for an account

La password verrà inviata via email.

Recupero della password

Recupera la tua password

La password verrà inviata via email.

-

-

- Categorie

- #iorestoacasa

- Agenda

- Archeologia

- Architettura

- Arte antica

- Arte contemporanea

- Arte moderna

- Arti performative

- Attualità

- Bandi e concorsi

- Beni culturali

- Cinema

- Contest

- Danza

- Design

- Diritto

- Eventi

- Fiere e manifestazioni

- Film e serie tv

- Formazione

- Fotografia

- Libri ed editoria

- Mercato

- MIC Ministero della Cultura

- Moda

- Musei

- Musica

- Opening

- Personaggi

- Politica e opinioni

- Street Art

- Teatro

- Viaggi

- Categorie

-

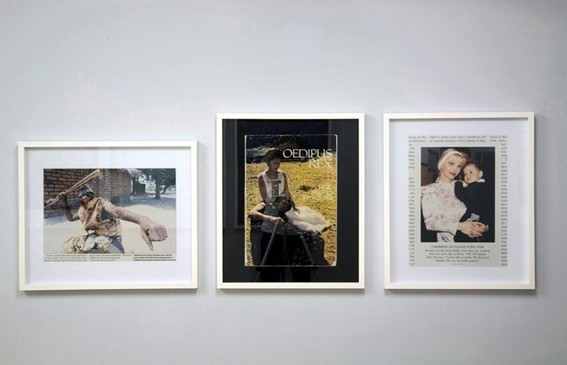

One of these things is not like the other things

Una collettiva incentrata unicamente sull’esclusione? Forse questo non è il solo obiettivo di una mostra che riunisce l’accurata selezione di opere di 24 artisti internazionali che, così presentate, ci pongono una domanda: quale di noi non è una di “noi”? Quale lavoro non fa parte di questa mostra?

Comunicato stampa

Segnala l'evento

Una collettiva incentrata unicamente sull’esclusione? Forse questo non è il solo obiettivo di una mostra che riunisce l’accurata selezione di opere di 24 artisti internazionali che, così presentate, ci pongono una domanda: quale di noi non è una di “noi”? Quale lavoro non fa parte di questa mostra? Quale di queste cose non è come le altre? (Si tratta sicuramente di più di una domanda. Ma siamo sicuri di intendere sempre “uno” quando diciamo “uno”?)

I visitatori, con a disposizione la pianta della galleria, potranno identificare l’opera d’arte che, a loro avviso, non corrisponde al tema della mostra. Non c’è alcun premio in palio e non si tratta né di un gioco né di un test per stabilire il quoziente intellettivo. O.O.T.T.I.N.L.T.O.T vuole essere un esperimento cognitivo in forma di mostra. Collocata all’interno di un discorso di democratica e totale inclusività (dalle leggi sull’immigrazione fino alla critica d’arte) che giustifica l’inclusione del lavoro B per il semplice fatto che A è già lì presente, O.O.T.T.I.N.L.T.O.T capovolge il principio fondamentale di questa ideologia: ci chiede di escludere piuttosto che includere.

Per alcune delle persone che hanno partecipato alla preparazione di questa mostra è stato piuttosto facile individuare il lavoro “intruso”. Per altri si è trattato invece di una sfida più complicata perché molteplici legami concettuali o formali con gli altri lavori cominciavano a manifestarsi nel momento in cui si identificava un’opera d’arte di un altro genere. “Almeno ci siamo divertiti”, hanno ammesso alla fine. Per un terzo gruppo il processo di esclusione è andato avanti a tal punto da indurli a rimuovere tutti i lavori dalla mostra perché nessuno di essi a loro parere ne faceva parte. Sebbene anche gli sforzi di quest’ultimo gruppo non siano stati privi di divertimento, la ricerca dell’esclusione si è conclusa nel raggiungimento del centro mancante della mostra.

Secondo Slavoj Zizek il centro mancante può costituire l’essenza della preparazione di una mostra. Egli stesso è privato della sua essenza nelle macchie di saliva presenti tra gli appunti presi da Ana Prvacki durante una delle sue lezioni. Benoît Maire ha bucato alcune pagine dell’Enciclopedia Francese di Filosofia da Husserl a Cartesio – questi fori contengono categorie e concetti riguardanti il modo di conoscere la realtà senza leggere la filosofia. Il disegno a parete di Pierre Bismuth contiene i segni dei movimenti della mano destra di Sofia Loren nel film “Peccato che sia una canaglia”. Positivo e negativo si scambiano i ruoli nei disegni di Gabriel Acevedo Velarde. Juozas Laivys ha trovato un nido di uccelli caduto da un albero, ma si potrà poi risistemare all’interno della mostra? Un fotogramma vuoto è rimasto nella tasca di Mario Garcia Torres per un mese, ora verrà proiettato su una parete per 3 mesi. Più di due domande vengono poste nelle due foto di Falke Pisano – se fossero state meno astratte se ce ne sarebbo state anche di più. La musica di Gintaras Didziapetris si può ascoltare solo di notte, quando nessuno può vedere i suoi acquerelli. Alcuni lavori contengono del colore. Alcuni sono in bianco e nero. Altri sono fuori spettro. Donelle Woolford è essa stessa una creatura spettrale, nonostante i suoi lavori scaturiscano dalla storia afro-americana. I ritratti di Loris Greaud sono scomparsi dalla tela. Ce ne siamo accorti? Chi può confermare che nulla è cambiato nel film di Aurelien Froment dall’ultima volta che lo abbiamo visto? Chi, per esempio, ha visto Marco Raparelli fare un buco nel muro? O Gabriel Lester concepire l’idea per uno dei suoi lavori più inconsueti? Chi ascolta le notizie della BBC il venerdì sera? E chi non ce l’ha fatta ad essere incluso nel comunicato stampa? Rosalind Nashashibi spesso ritrae processi mentali senza un effettivo ritratto – questi possono aiutare. Un foglio di carta trasparente che stava cadendo dal tavolo viene preso e sepolto da un laser nella sfera di vetro di Ryan Gander. Mariana Castillo Deball ha lavorato con una macchina del tempo in Serbia per realizzare disegni che trascendessero il tempo. Se non si trattasse di un aeroporto João Penalva non avrebbe calpestato l’ombra del tempo. Torreya Cummings portava occhiali con tre lenti – essi modificano percezione e aspetto. Le scarpe non sono ammesse nel disegno di Darius Miksys. La polvere delinea dei paesaggi nelle foto e oggetti di Julieta Aranda. Le sue parole crociate sono aperte a parole che le incrocino. Non accadono solo cose curiose. Una parte di un lavoro di Luca Trevisani è stata rimossa dall’installazione di cui inizialmente faceva parte e combinata con altre. Rorschach non è più un test – con Jason Kalogiros due elementi vengono rappresentati l’uno contro l’altro. Michael Portnoy sta ancora cantando una cover della canzone del Cookie Monster. Non poteva esserci miglior conclusione del centro mancante nell’uovo di Raphael Julliard.

La mostra è curata da Raimundas Malasauskas

A group exhibition exclusively based on exclusion? Perhaps this is not the sole aim of this show, which includes a number of carefully selected works by 24 international artists that together pose one question: which one of us is not one of “us”? Which work does not belong to the show? Which one of these things is not like the other things? (It’s definitely more than one question, but do we always mean one when we say one?).

Visitors are welcome to use gallery maps and single out an artwork they find does not correspond with the rest of the show. No prize is gained from this activity though. Neither a game, nor an IQ test, O.O.T.T.I.N.L.T.O.T positions itself as a cognitive experiment in the format of an exhibition. Situating itself within a discourse of democratic all-inclusiveness, which embraces everything from immigration policies to writing on art, and which justifies the inclusion of work B by the simple fact that A is already there, O.O.T.T.I.N.L.T.O.T inverts the main principle of this ideology by asking to exclude rather than include.

Some of the participants in the exhibition rehearsals were able to quickly and easily determine which works should be excluded. Others found it difficult because all kinds of conceptual or formal links with other works would materialize as soon as they identified an artwork of a different order. “At least we had some fun,” these visitors concluded. For a third group, the process of exclusion went so far as to remove all the works in the show; supposedly none of the parts fit with the whole. Although this group’s efforts were not devoid of fun either, their quest for exclusion ended up attaining the show’s missing center.

According to Slavoj Zizek, the missing center may constitute the essence of exhibition making, yet Zizek himself is deprived of his own essence in spots of spittle he projected onto notes taken by Ana Prvacki during one of his lectures. Benoît Maire left holes in the French Encyclopedia of Philosophy from Husserl to Decartes—these contain categories and concepts related to how we can experience reality without reading philosophy. A wall drawing by Pierre Bismuth contains traces of Sofia Loren right hand movement in the film “Too Bad She Is Bad.” Positive and negative exchange roles in drawings by Gabriel Acevedo Velarde. Juozas Laivys found a bird’s nest that dropped out a tree, but will it stick to the show? One frame of a blank film stayed in Mario Garcia Torres’ pocket for a month, now it is projected on the wall for three. More than two questions are being asked in two photos by Falke Pisano—if they were less abstract there would be even more. Gintaras Didziapetris’ music only plays at night when no one sees his water-colors. Some works contain color. Some are black and white. A few exceed spectrum. Donelle Woolford is a spectral being herself, although her works stem from the history of African-Americans. Portraits by Loris Greaud have disappeared from the canvas. Did we see it happen? Who took hands off of your eyes too soon? Can anyone confirm that nothing has changed in Aurelien Froment’s film since last time we saw it? Who saw when Marco Raparelli broke the hole in the wall, for example? Or when Gabriel Lester came up with an idea for his strangest piece ever? Who here listens to BBC News on Friday night? And who didn’t make it to the press release? Rosalind Nashashibi sometimes portrays thought processes without an actual portrait— they can help. A transparent sheet of paper that was falling off the table is captured and laser-engraved in Ryan Gander’s glass ball. Mariana Castillo Deball worked with a time machine in Serbia to produce drawings that transcend timelessness. If it were not in an airport, Joao Penalva would not have stepped on time’s shadow. Torreya Cummings wore glasses with three lenses— they change perception and looks. Shoes are not allowed in Darius Miksys’ drawing though. The unsettled dust of Sci-Fi books defines the landscape of Julieta Aranda’s objects and photos. Her crosswords are open for words to cross themselves. Not only strange things happen. A fragment of a work of Luca Trevisani was removed from his installation, cut off of its ties and entangled with lives of other parts. Rorschach is not a test anymore—Jason Kalogiros runs two sides against themselves. Michael Portnoy is still singing a cover version of Cookie Monster’s song. The missing center of an egg by Raphael Julliard finishes the sentence with the hole instead of the whole. Full stop has never been fuller.

The show is curated by Raimundas Malasauskas

I visitatori, con a disposizione la pianta della galleria, potranno identificare l’opera d’arte che, a loro avviso, non corrisponde al tema della mostra. Non c’è alcun premio in palio e non si tratta né di un gioco né di un test per stabilire il quoziente intellettivo. O.O.T.T.I.N.L.T.O.T vuole essere un esperimento cognitivo in forma di mostra. Collocata all’interno di un discorso di democratica e totale inclusività (dalle leggi sull’immigrazione fino alla critica d’arte) che giustifica l’inclusione del lavoro B per il semplice fatto che A è già lì presente, O.O.T.T.I.N.L.T.O.T capovolge il principio fondamentale di questa ideologia: ci chiede di escludere piuttosto che includere.

Per alcune delle persone che hanno partecipato alla preparazione di questa mostra è stato piuttosto facile individuare il lavoro “intruso”. Per altri si è trattato invece di una sfida più complicata perché molteplici legami concettuali o formali con gli altri lavori cominciavano a manifestarsi nel momento in cui si identificava un’opera d’arte di un altro genere. “Almeno ci siamo divertiti”, hanno ammesso alla fine. Per un terzo gruppo il processo di esclusione è andato avanti a tal punto da indurli a rimuovere tutti i lavori dalla mostra perché nessuno di essi a loro parere ne faceva parte. Sebbene anche gli sforzi di quest’ultimo gruppo non siano stati privi di divertimento, la ricerca dell’esclusione si è conclusa nel raggiungimento del centro mancante della mostra.

Secondo Slavoj Zizek il centro mancante può costituire l’essenza della preparazione di una mostra. Egli stesso è privato della sua essenza nelle macchie di saliva presenti tra gli appunti presi da Ana Prvacki durante una delle sue lezioni. Benoît Maire ha bucato alcune pagine dell’Enciclopedia Francese di Filosofia da Husserl a Cartesio – questi fori contengono categorie e concetti riguardanti il modo di conoscere la realtà senza leggere la filosofia. Il disegno a parete di Pierre Bismuth contiene i segni dei movimenti della mano destra di Sofia Loren nel film “Peccato che sia una canaglia”. Positivo e negativo si scambiano i ruoli nei disegni di Gabriel Acevedo Velarde. Juozas Laivys ha trovato un nido di uccelli caduto da un albero, ma si potrà poi risistemare all’interno della mostra? Un fotogramma vuoto è rimasto nella tasca di Mario Garcia Torres per un mese, ora verrà proiettato su una parete per 3 mesi. Più di due domande vengono poste nelle due foto di Falke Pisano – se fossero state meno astratte se ce ne sarebbo state anche di più. La musica di Gintaras Didziapetris si può ascoltare solo di notte, quando nessuno può vedere i suoi acquerelli. Alcuni lavori contengono del colore. Alcuni sono in bianco e nero. Altri sono fuori spettro. Donelle Woolford è essa stessa una creatura spettrale, nonostante i suoi lavori scaturiscano dalla storia afro-americana. I ritratti di Loris Greaud sono scomparsi dalla tela. Ce ne siamo accorti? Chi può confermare che nulla è cambiato nel film di Aurelien Froment dall’ultima volta che lo abbiamo visto? Chi, per esempio, ha visto Marco Raparelli fare un buco nel muro? O Gabriel Lester concepire l’idea per uno dei suoi lavori più inconsueti? Chi ascolta le notizie della BBC il venerdì sera? E chi non ce l’ha fatta ad essere incluso nel comunicato stampa? Rosalind Nashashibi spesso ritrae processi mentali senza un effettivo ritratto – questi possono aiutare. Un foglio di carta trasparente che stava cadendo dal tavolo viene preso e sepolto da un laser nella sfera di vetro di Ryan Gander. Mariana Castillo Deball ha lavorato con una macchina del tempo in Serbia per realizzare disegni che trascendessero il tempo. Se non si trattasse di un aeroporto João Penalva non avrebbe calpestato l’ombra del tempo. Torreya Cummings portava occhiali con tre lenti – essi modificano percezione e aspetto. Le scarpe non sono ammesse nel disegno di Darius Miksys. La polvere delinea dei paesaggi nelle foto e oggetti di Julieta Aranda. Le sue parole crociate sono aperte a parole che le incrocino. Non accadono solo cose curiose. Una parte di un lavoro di Luca Trevisani è stata rimossa dall’installazione di cui inizialmente faceva parte e combinata con altre. Rorschach non è più un test – con Jason Kalogiros due elementi vengono rappresentati l’uno contro l’altro. Michael Portnoy sta ancora cantando una cover della canzone del Cookie Monster. Non poteva esserci miglior conclusione del centro mancante nell’uovo di Raphael Julliard.

La mostra è curata da Raimundas Malasauskas

A group exhibition exclusively based on exclusion? Perhaps this is not the sole aim of this show, which includes a number of carefully selected works by 24 international artists that together pose one question: which one of us is not one of “us”? Which work does not belong to the show? Which one of these things is not like the other things? (It’s definitely more than one question, but do we always mean one when we say one?).

Visitors are welcome to use gallery maps and single out an artwork they find does not correspond with the rest of the show. No prize is gained from this activity though. Neither a game, nor an IQ test, O.O.T.T.I.N.L.T.O.T positions itself as a cognitive experiment in the format of an exhibition. Situating itself within a discourse of democratic all-inclusiveness, which embraces everything from immigration policies to writing on art, and which justifies the inclusion of work B by the simple fact that A is already there, O.O.T.T.I.N.L.T.O.T inverts the main principle of this ideology by asking to exclude rather than include.

Some of the participants in the exhibition rehearsals were able to quickly and easily determine which works should be excluded. Others found it difficult because all kinds of conceptual or formal links with other works would materialize as soon as they identified an artwork of a different order. “At least we had some fun,” these visitors concluded. For a third group, the process of exclusion went so far as to remove all the works in the show; supposedly none of the parts fit with the whole. Although this group’s efforts were not devoid of fun either, their quest for exclusion ended up attaining the show’s missing center.

According to Slavoj Zizek, the missing center may constitute the essence of exhibition making, yet Zizek himself is deprived of his own essence in spots of spittle he projected onto notes taken by Ana Prvacki during one of his lectures. Benoît Maire left holes in the French Encyclopedia of Philosophy from Husserl to Decartes—these contain categories and concepts related to how we can experience reality without reading philosophy. A wall drawing by Pierre Bismuth contains traces of Sofia Loren right hand movement in the film “Too Bad She Is Bad.” Positive and negative exchange roles in drawings by Gabriel Acevedo Velarde. Juozas Laivys found a bird’s nest that dropped out a tree, but will it stick to the show? One frame of a blank film stayed in Mario Garcia Torres’ pocket for a month, now it is projected on the wall for three. More than two questions are being asked in two photos by Falke Pisano—if they were less abstract there would be even more. Gintaras Didziapetris’ music only plays at night when no one sees his water-colors. Some works contain color. Some are black and white. A few exceed spectrum. Donelle Woolford is a spectral being herself, although her works stem from the history of African-Americans. Portraits by Loris Greaud have disappeared from the canvas. Did we see it happen? Who took hands off of your eyes too soon? Can anyone confirm that nothing has changed in Aurelien Froment’s film since last time we saw it? Who saw when Marco Raparelli broke the hole in the wall, for example? Or when Gabriel Lester came up with an idea for his strangest piece ever? Who here listens to BBC News on Friday night? And who didn’t make it to the press release? Rosalind Nashashibi sometimes portrays thought processes without an actual portrait— they can help. A transparent sheet of paper that was falling off the table is captured and laser-engraved in Ryan Gander’s glass ball. Mariana Castillo Deball worked with a time machine in Serbia to produce drawings that transcend timelessness. If it were not in an airport, Joao Penalva would not have stepped on time’s shadow. Torreya Cummings wore glasses with three lenses— they change perception and looks. Shoes are not allowed in Darius Miksys’ drawing though. The unsettled dust of Sci-Fi books defines the landscape of Julieta Aranda’s objects and photos. Her crosswords are open for words to cross themselves. Not only strange things happen. A fragment of a work of Luca Trevisani was removed from his installation, cut off of its ties and entangled with lives of other parts. Rorschach is not a test anymore—Jason Kalogiros runs two sides against themselves. Michael Portnoy is still singing a cover version of Cookie Monster’s song. The missing center of an egg by Raphael Julliard finishes the sentence with the hole instead of the whole. Full stop has never been fuller.

The show is curated by Raimundas Malasauskas

02

luglio 2008

One of these things is not like the other things

Dal 02 luglio al 20 settembre 2008

arte contemporanea

Location

1/9 – UNOSUNOVE ARTE CONTEMPORANEA

Roma, Via Degli Specchi, 20, (Roma)

Roma, Via Degli Specchi, 20, (Roma)

Orario di apertura

da martedì a venerdì ore 11-19

sabato ore 15-20 (la mattina su appuntamento)

Vernissage

2 Luglio 2008, ore 19.00

Autore

Curatore